Understanding Social Divisions in the United States

Based on research by Klaus Desmet, Ignacio Ortuño-Ortín, and Romain Wacziarg

There is growing concern over rising social divisions in many Western countries, especially in the United States. Many have noted the importance of culture wars in the public sphere, arguing that there is growing social animosity due to disagreements over issues such as abortion, minority rights, the role of religion, the extent of redistribution, and a host of other moral, cultural, and political issues. This leads to the belief that societies are becoming more and more socially polarized.

If we focus on the case of the United States, there is a broad consensus that partisan polarization has increased in recent decades. One expression of the widening partisan divide is the increased correlation between an individual’s policy views and voting behavior (Fiorina and Abrams, 2008): knowing someone’s views on issues has become more predictive of political party affiliation. Another expression is the rise in affective polarization, with an increasing number of Americans expressing a dislike of voters of the other party (Iyengar et al., 2019; Boxell et al., 2022). There is less consensus about whether growing partisan polarization reflects actual deep divisions between Americans. When analyzing disagreement on different issues among the overall population, Ansolabehere et al. (2006) talk about a ‘Purple America’ and Fiorina et al. (2005) about the ‘Myth of a Polarized America’. In contrast, Abramowitz and Saunders (2008) claim that ideological polarization has increased substantially among the mass public since the 1970s. In a recent paper, entitled “Latent Polarization”, we bring a new perspective to this topic. We find that social polarization has been high and relatively stable for decades.

Latent Polarization

We introduce a new way to measure the deep, underlying divisions in society by grouping people based on shared values and beliefs. This approach provides insight into how different segments of society are formed, even when these divisions are not immediately visible, like those defined by political parties or social classes. By analyzing survey data from the last four decades, the research explores whether American society has become more polarized over time and compares these underlying divisions with the visible political polarization we often see today.

Measuring Social Divisions: The method used to measure these divisions is based on the idea that people prefer to interact with those who share similar values—a concept known as homophily. Researchers use responses to about 200 questions from the World Values Survey to determine individuals’ cultural, moral, and political value positions. We use dimension reduction techniques (principal components and autoencoder neural networks), and algorithms (such as k-means) to classify individuals into groups based on those positions. The idea is to find the groups that individuals would fall into if they tried to interact with other individuals similar to themselves. Furthermore, these divisions are stable in the sense that no one in a group prefers to interact more with those in the other group than with those in their own group. This approach reveals a clearer picture of how American society is divided beneath the surface.

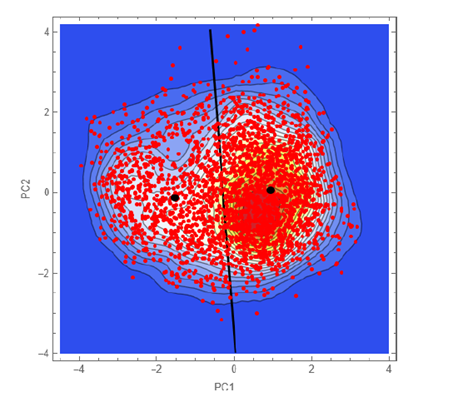

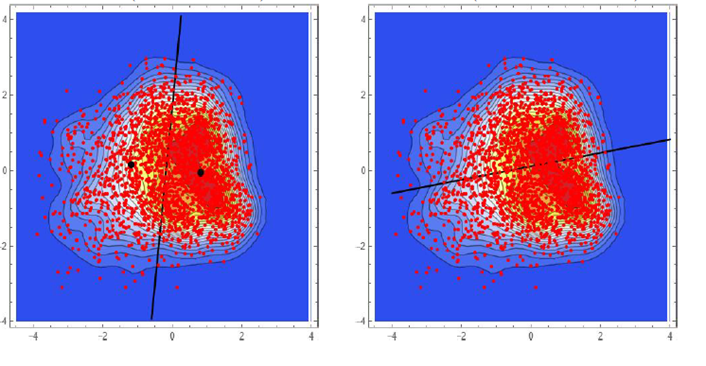

Figure 1 shows an example of dividing individuals into two cultural groups, using data from the 2017 survey. The one on the left represents the “progressive” group and the one on the right the “conservative” group. Using Principal Components, a very conventional dimension reduction technique, the positions of individuals given by the answers to 200 questions have been reduced to two dimensions. The first dimension reflects moral and religious values. The second dimension is based on the answers to questions about institutions, economics and redistribution.

Figure 1. Division of individuals into two groups in 2017

Our key findings can be summarized as follows:

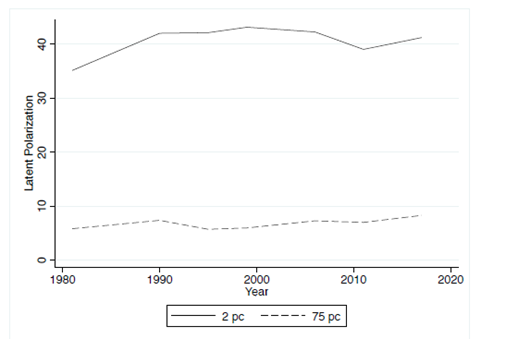

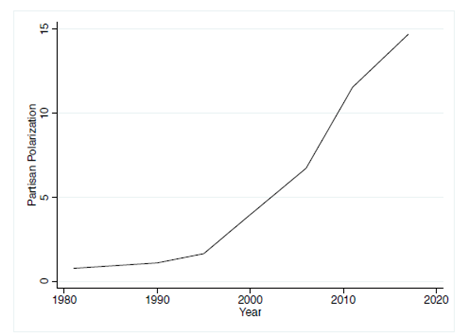

Latent vs. Partisan Polarization: Our research distinguishes between “latent polarization,” which reflects deep-seated values that divide people, and “partisan polarization,” which refers to the political divide between the major parties. Latent polarization in the United States has remained relatively high but stable over the last 40 years, indicating that society’s foundational value-based divisions have not widened. However, partisan polarization, particularly between Democratic and Republican voters, has been steadily increasing since the 1990s. This increase is making the political divide align more closely with the underlying divisions in people’s values.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of latent polarization, in the case of reducing the 200 questions into only two dimensions or 75 dimensions.

Figure 2. Evolution of Latent Polarization in the USA

Stable Latent Divisions: Although there is a perception that Americans are becoming more divided, the study found that the underlying value-based clusters have remained stable over time. Since the 1980s, the two main dimensions of value-based division have focused on religious and moral issues, as well as social capital (trust in institutions and civic engagement). Economic factors, surprisingly, have not been the primary drivers of these divisions.

Changes in Partisan Polarization: While latent polarization remained high but unchanged, partisan polarization—how strongly voters of different political parties differ—has grown significantly. In the 1980s, there was little difference between Democrats and Republicans in terms of core values. However, since around 2000, the gap has widened, with party affiliation becoming a stronger reflection of deeper values-based clusters. This means that political parties are now more representative of the underlying cultural and moral divisions in society than they were in the past.

Figure 3. Partisan Polarization: 1981 to 2017

The Nature of Divisions: The study also compared latent polarization with divisions based on other social identifiers like race, gender, income, and religion. Interestingly, it found that divisions based on race, gender, or income are much less pronounced compared to divisions based on core values. This means that if Americans grouped themselves purely based on shared values rather than demographics or political affiliation, they would be far more polarized.

A Shift in Social Cleavages: In the earlier years of the study (1980s and early 1990s), there was an alternative way society could have been divided, one that was more aligned with income differences. However, by the mid-1990s, the dominant way of dividing the U.S. population had shifted firmly to cultural and religious lines, reflecting the increasing importance of moral values over economic status in defining social divisions.

Figure 4 shows two possible divisions of individuals in 1981. The first is a division based on dimension 1, which represents moral and religious values, while the second division is based on dimension 2, which represents institutional and economic issues. This second type of division cannot be found in the 2017 data.

Figure 4. Different possible divisions in 1981

These findings suggest that, while Americans may perceive a growing divide, the deep divisions have always been there—they are just more aligned with political identities. The rise in partisan polarization does not necessarily mean that Americans have become more different from each other; instead, political parties have become better at reflecting the underlying social divisions that have existed for decades. This growing alignment between latent values and political affiliation could help explain the increased social and political tensions in recent years. Thus, the study provides a nuanced view of American polarization, showing that while underlying cultural and moral divisions are stable, the way these divisions manifest in politics has become more pronounced, leading to a perception of greater division.

Further Reading:

Abramowitz, A. I. and K. L. Saunders (2008). Is Polarization a Myth? Journal of Politics 70 (2), 542–555.

Ansolabehere, S., J. Rodden, and J. M. Snyder (2006). Purple America. Journal of Economic Perspectives 20 (2), 97–118

Boxell, L., M. Gentzkow, and J. M. Shapiro (2022, 01). Cross-Country Trends in Affective Polarization. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–60.

Desmet, K., Ortuño-Ortín, I. and R. Wacziarg, (2024) “Latent Polarization” (https://bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/people.smu.edu/dist/5/322/files/2024/07/LatentPolarization.pdf)

Fiorina, M. P., S. J. Abrams, and J. C. Pope (2005). Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America. New York: Pearson Longman

Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S. J. Westwood (2019). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1), 129–146.

About the authors:

- Klaus Desmet is Full Professor at the Department of Economics & Cos School of Business at the Southern Methodist University, and Research Associate, NBER, UC3M and Research Affiliate CEPR. Website: https://people.smu.edu/kdesmet/

- Ignacio Ortuño-Ortín is Full Professor at the Economics Department of Carlos III University. Website: https://sites.google.com/view/ignacioortuno/about?authuser=0

- Romain Wacziarg is a professor of economics at UCLA Anderson School of Management and Research Associate, NBER. Website: https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty-and-research/global-economics-and-management/faculty/wacziarg