How electoral competition can hinder the search for good reforms

Based on research by Álvaro Delgado Vega, Wioletta Dziuda and Antoine Loeper

In modern representative democracies, parties control the policymaking process, and are typically better informed than the voters about the consequences of different policies. In our increasingly polarized world, they sometimes use this procedural and informational power to pursue partisan policy objectives at the expense of voters’ welfare.

Since voters learn about the consequences of a reform only after it has been implemented and can influence policies only indirectly and infrequently via elections, repealing bad laws is as important as enacting good ones. This observation begs the following question: Do repeals occur when and only when voters have collectively learned about the negative consequences of a reform?

A familiar tale about reforms: common good or partisan grab?

There are many issues in politics in which there is a consensus about the outcomes that a reform should achieve. However, in a complex and changing world, it is hard for voters to predict the consequences of different policies.

In this context of policy uncertainty, the best one can reasonably expect from representative democracy is that different reforms be tried out, and those that turn out to deliver bad results be repealed. Specifically, suppose a reform fails to achieve its stated goals a few years after it is enacted, even if the incumbent fails to recognize its failure. In that case, it is reasonable to expect that the opposition promises to repeal it, that the voters elect the opposition based on this promise and that the opposition carries it out. This hypothetical scenario suggests that even an institutionally powerless opposition can help society search for better educational policies by announcing its intent to repeal bad reforms.

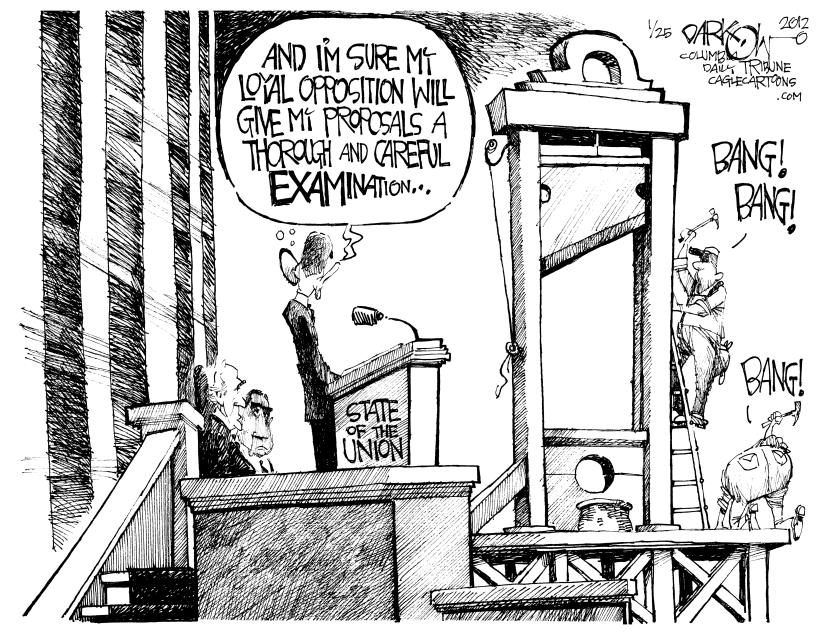

However, the way repeals are used in reality often departs from this optimistic scenario and follows instead the following familiar tale. The incumbent party presents a new reform and argues that it will improve the lives of most citizens. The opposition party immediately challenges this narrative, accusing the incumbent party of partisan overreach. Neither claim can easily be verified or falsified by the voters, because they do not fully grasp the consequences of the new law, especially in the short term. Right after the reform is passed—and thus before enough information has been gathered to determine whether it is socially desirable— the opposition party makes a pledge to repeal it if elected, hoping that this announcement will pay off in the next election.

An example: educational reform in Spain

In 2001, the conservative government of José María Aznar attempted to reform the Spanish education system, which culminated in a proposal for a new Organic Law of Education: the Ley Orgánica de Calidad de la Educación (LOCE). Aznar’s government encountered strong resistance, not only from the main opposition party, the Socialist Party (PSOE), but also from teacher unions and other organizations. The debate over the reform was deeply polarized, and by the 2004 general elections, Aznar’s government had not yet implemented the LOCE. After the PSOE won the general elections, the new government suspended the law before it could take effect, fulfilling its promise to repeal it.

How common is this sequence of events in Spanish politics? The next table presents Spain’s main educational reforms since the transition to democracy. It shows that in the last decades, every law has been deeply contested by the opposition and the opposition often promised to repeal the reforms as soon as they were announced.

| Reform | Party in Power | Opposition’s Position |

|---|---|---|

| LODE (1985) | PSOE (Felipe González) | The PP criticized some aspects, but did not immediately promise to repeal it. |

| LOGSE (1990) | PSOE (Felipe González) | The PP opposed LOGSE from the outset and by the mid-1990s, promised to repeal it. |

| LOCE (2001, not enacted) | PP (José María Aznar Rajoy) | The PSOE opposed the LOCE from the outset and repealed it before implementation. |

| LOCE (2006) | PSOE (José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero) | The PP opposed the LOCE from the outset. |

| LOE (2006) | PSOE (José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero) | The PP criticized the LOE after seeing its effects and promised to repeal it. |

| Lomce (2013) | PP (Mariano Rajoy) | The PSOE opposed the Lomce from the outset. |

| Lomloe (2020) | PSOE (Pedro Sánchez) | The PP and Vox opposed the Lomloe from the outset. |

While in some cases (e.g., LODE and LOGSE) the opposition came gradually to oppose the law, in other cases the promise of repeal was immediate, and the opposition criticized these laws as ideologically driven (Lomce, Lomloe).

Only a Spanish story? Not really. For instance, in the U.S., Republicans pledged to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) right after it was voted in by Congress, arguing that it was a partisan overreach by the Democrats. When presenting the bill, President Obama said:

“I have no doubt that these reforms would greatly benefit Americans from all walks of life, as well as the economy as a whole.”

The Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell instead claimed:

“In one of the most divisive legislative debates in modern history, Democrats decided to go the partisan route and blatantly ignore the will of the people.”

Key questions

Our study seeks to answer the following questions:

- Under what circumstances do the opposition party abuse repeal promises and use them for electoral gains, even when the newly enacted reform is beneficial?

- How do such electorally motivated repeal promises affect the incumbent party’s policy decisions? Does the threat of a repeal discourage the implementation of partisan policies, or do they also deter the implementation of socially beneficial ones?

The repeal game

To analyze these questions, we develop a parsimonious model that captures the interactions between the incumbent, the opposition, and the voters. Our model has three main building blocks:

- There are two classes of reforms: common-interest (beneficial to the voters and both parties) and partisan (beneficial to the incumbent and harmful to the voters and the opposition)

- The incumbent decides whether to enact the reform. The opposition reacts by promising to repeal it or not if elected. The voter observes the parties’ decisions before the next election.

- The voter does not know whether the reform enacted by the incumbent is common-interest or partisan. Since parties are better informed (they are “policy specialists”) the voters can only infer the quality of the reform by observing the parties’ decisions.

Indiscriminate obstructionism

Scenario 1: Efficient Repeals. To better isolate the consequences of the opposition’s strategic behavior, we first consider a benchmark case in which the incumbent behaves according to its own interests (its preferences includes both electoral and policy objectives), but the opposition is assumed to behave in the best interests of the voter and promises to repeal only partisan reforms.

In this benchmark case, efficient repeals have three virtues. First, they inform the voters when the incumbent has implemented a partisan reform. Second, when a partisan reform has been implemented, they allow the voter to get rid of it by electing the opposition. Third, they deter the incumbent from enacting a partisan reform in the first place, by fear of the electoral consequences of the promise of a repeal by the opposition.

Scenario 2: Strategic Repeals. In this more realistic scenario, the incumbent and the opposition both behave according to their own (policy and electoral) interests. The game theoretic analysis reveals that the oppositions’ policy objectives induce it to repeal only partisan reforms, as in the benchmark case, but its electoral objectives give it incentives to also repeal common-interest reforms. When its electoral motivation is strong enough, the opposition benefits from promising to repeal beneficial reforms because the uninformed (but rational) voter tend to reward the opposition in the next election for its critical stance against the government. Thus, the voter’s ignorance allows the opposition to present itself (falsely) as a defender of voter interests, and the opposition engages in indiscriminate obstructionism.

The incumbent’s reaction: Interestingly, the model shows that the opposition’s strategic repeals create in turn perverse incentives for the incumbent. Depending on the equilibrium on which players coordinate, these perverse incentives can take two different forms. In one equilibrium, because the voter knows that the opposition promises to repeal both kinds of reform, she knows that its announcements are not very informative about the nature of the reform. As a result, its repeals lose their deterring effect, and the incumbent takes advantage of this by enacting mot only common-interest but also partisan reforms. In the other equilibrium, the opposition’s repeals remain sufficiently deterrent and the incumbent enacts neither partisan nor common-interest reforms. Thus, depending on how parties and voters coordinate their expectations, the obstructionist bias of the opposition either fails to filter out bad reforms, or leads to complete gridlock.

Conclusion

In summary, our model illustrates how the informational gap between voters and politicians induces the opposition to engage in indiscriminate obstructionism, and how this electorally motivated strategy of the opposition distorts the incentives of the incumbent, by either inducing it to implement both good and bad reforms, or instead to deter it from implementing any reform at all.

About the Authors:

Álvaro Delgado Vega is Assistant Professor of Economics at the Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago. His research interests are in political economy, especially on electoral competition and accountability.

https://sites.google.com/view/alvarodelgadovega/

Wiola Dziuda is Associate Professor of Economics at the Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago. Her research interests are in political economy, especially on legislative bargaining and political scandals.

https://sites.google.com/site/dziudawiola/home

Antoine Loeper is Associate Professor at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. His research focuses on political economy, with a particular emphasis on legislative bargaining.

https://sites.google.com/view/antoineloeper/

Further Reading:

Delgado Vega, A., W. Dziuda, and A. Loeper, “The Politics of Repeals”, unpublished manuscript.