Brazil’s experience shows that strict bans can effectively reduce both active and passive smoking

Based on research by Camila Steffens and Paula Carvalho Pereda

Interventions aimed at preventing smoking addiction and its associated harmful effects have gained increasing global adoption, largely due to the influence of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control introduced in 2005. This international treaty has been endorsed by 180 countries, promoting various measures to combat tobacco use. These measures include, among others, advertising bans, health warnings about smoking risks, cigarette taxation and price controls, smoking cessation programs, and smoking bans in public spaces.

Economic Reasoning of Smoking Control Policies

From an economic perspective, these interventions can be sustained by addressing various market failures. For example, banning cigarette advertising and promoting the dissemination of smoking-related health warnings are designed to reduce information asymmetries. Even under the assumption that individuals make informed and rational choices when deciding to smoke, policies designed to reduce cigarette consumption can still be justified by the substantial social costs imposed on healthcare systems and public finances. In this context, cigarette taxation has emerged as a widely used tool, often viewed as a Pigouvian tax intended to internalize the external marginal costs of smoking.

In their comprehensive review, DeCicca, Kenkel, and Lovenheim (2022) highlight the challenges involved in estimating the true costs of smoking and determining which factors should be considered in these calculations. These should include, for example, fiscal externalities such as publicly subsidized healthcare expenditures and reduced labor productivity among smokers. But there are also arguments for considering the negative effects of smoking on birth weight and child development, the health impacts of secondhand smoke, among others. While there is no clear consensus on the optimal tax level, a large body of research finds that, although tax increases are largely passed through to consumer prices, they tend to have only modest effects on smoking behavior. As a result, the inelastic demand for cigarettes generates a steady source of public revenue, which can help offset the fiscal costs linked to smoking-related externalities.

However, given that pricing policies alone have proven insufficient to significantly reduce smoking rates, attention has shifted toward more targeted interventions. An important market failure arises from the externalities faced by non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke in public spaces. A straightforward response is to simply transfer property rights over public air to non-smokers, which has led to the widely adopted policy known as smoking bans or smoke-free areas. These bans can be limited to specific places —such as workplaces or bars and restaurants—or implemented more comprehensively, applying to all enclosed or partially enclosed public places, often eliminating smoking designated areas (i.e., smoking lounges).

Effects of Smoking Bans

Evidence shows that smoking bans effectively lower secondhand smoke exposure in targeted areas. For example, Da Mata and Drugowick (2024) found that these bans reduced exposure among pregnant women working in the hospitality sector, leading to improved birth outcomes in Brazil. However, Adda and Cornaglia (2010) highlighted that the net effects on non-smokers are uncertain, depending on whether the bans mitigate consumption or simply displace it to non-restricted areas. In their study of the United States, they observed that smoking bans shifted smoking from public to private spaces, increasing children’s exposure to smoke at home and causing adverse health effects.

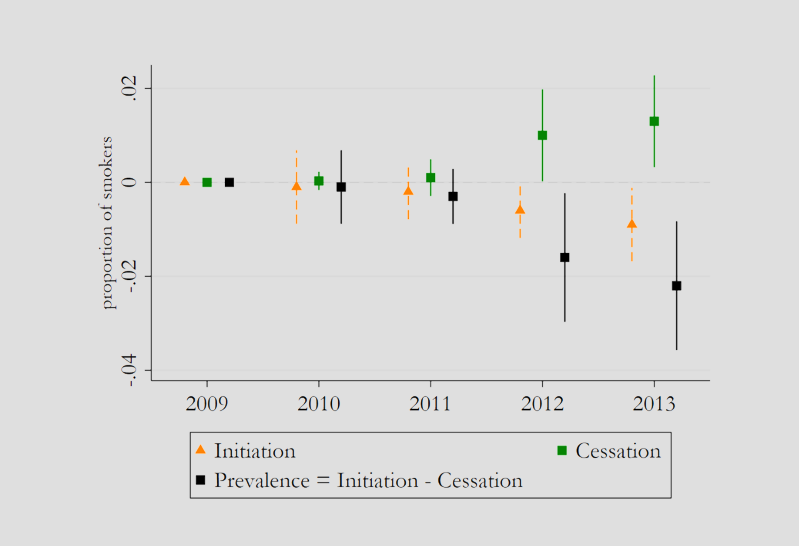

Thus, while reducing smoking prevalence is not the primary objective of smoke-free policies, their overall effectiveness ultimately depends on this first-order effect, which remains under debate. Most studies, focusing on Europe and the U.S., have found limited or inconclusive effects. In a recent study, we contribute to this debate by providing novel evidence from Brazil (Steffens and Pereda, 2025). Between 2009 and 2013, several states and state capitals adopted strict smoking bans covering all enclosed or partially enclosed public places, eliminating smoking lounges and introducing the enforcement of the policy. This policy was later implemented at the national level in 2014. Comparing smoking prevalence among young adults in state capitals with strict bans to those in capitals without them, we find that the policy led to an 18% reduction in smoking prevalence after four years.

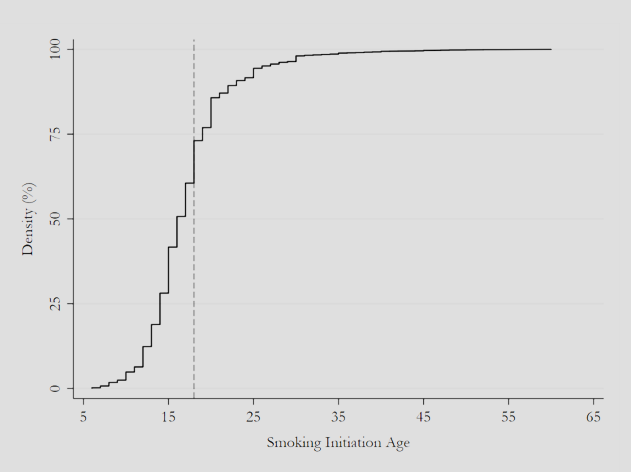

Our focus on young adults is motivated by two main factors that help explain how this policy may influence smoking behavior. First, smoking bans may affect initiation—which typically happens at early ages, as illustrated in Figure 1— by limiting exposure to social triggers from peers. Second, these policies can increase the marginal cost of smoking by limiting access to smoking areas and reducing social acceptance, thus potentially encouraging cessation. Prior research on cessation patterns often includes an unrestricted sample of adults. However, given the addictive nature of smoking, cessation effects among long-time smokers tend to materialize slowly and may require substantial shocks, which could explain the mixed findings in the literature. In contrast, during the early stages of addiction, the increased costs imposed by smoking bans may be sufficient to stimulate quitting.

Figure 1. Cumulative distribution of smoking initiation age in Brazil (2013)

We explore these mechanisms, showing that 60% of the reduction in smoking prevalence is driven by cessation among young adults who began smoking just before the bans were implemented, with the remaining effects attributed to reduced initiation. Our main results are summarized in Figure 2. The relatively modest effects on initiation may stem from the fact that individuals are often introduced to smoking in environments not targeted by the bans. This is because initiation typically happens before the minimum legal age to purchase cigarettes and alcohol, which is 18 in Brazil. In fact, we observed that nearly 73% of smokers in our sample began regularly smoking before this age (Figure 1, vertical dashed line).

Figure 2. Effects of Smoking Bans on Smoking Behavior Among Young Adults in Brazil

Note: Figure derived from Table 4 of our study. The reduction in prevalence is 2.2 percentage points, representing an 18% decrease from the baseline prevalence of 12%.

What Can We Learn from the Brazilian Experience?

Our study is among the first to evaluate the effects of smoking bans in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite bearing a disproportionate share of smoking-related costs, anti-smoking policies in LMICs have been largely underexplored, and their implementation presents unique challenges that differ from those in high-income countries. For example, the widespread availability of illicit markets offering cheaper, untaxed alternatives suggests that the impact of pricing policies on smoking prevalence may be less pronounced in LMICs. Our findings suggest that smoking bans can serve as an effective policy alternative in such contexts. Importantly, we also highlight the critical role of enforcement in determining the success of smoking bans in LMICs. In Brazil, the impact of the bans was driven by capitals where policies were effectively enforced, while no significant effects were observed in areas with weak enforcement.

The Brazilian experience also provides valuable insights for developed countries still struggling with high smoking prevalence. Brazil is recognized as a success story on tobacco control by the WHO, with smoking prevalence dropping from 18% in 2008 to 12.6% by 2019. Although most countries had implemented some form of smoking ban, only half of them had adopted comprehensive smoke-free areas. For example, in many European countries, smoking lounges are still allowed, or smoking bans do not apply to smaller pubs and bars. These policies often do not extend to outdoor areas of bars or restaurants or public transport stations, even when they are partially enclosed. Our findings strengthen the case for implementing comprehensive smoking bans to reduce both active and passive smoking.

About the Authors:

Camila Steffens is a Postdoctoral Researcher at ZEW – Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research working in the field of labor economics and causal inference, also interested in health and development economics. She completed her PhD in Economics from the University Carlos III de Madrid in 2024.

https://sites.google.com/site/camilastfs/home

Paula Carvalho Pereda is a Professor of Economics at the University of São Paulo working on policy evaluation, environmental economics, health economics, and gender economics.

https://sites.google.com/site/paulapereda/

Further Reading:

Steffens, C., & Pereda, P. C. (2025). “Dynamic responses to smoking bans: Evidence from young adults in a developing country.” Journal of Development Economics, 174, p. 103-442.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2024.103442

References:

Adda, J., & Cornaglia, F. (2010). “The effect of bans and taxes on passive smoking.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1), p. 1-32.

Da Mata, D., & Drugowick, P. (2024). “The consequences of health mandates on infant health: Evidence from a smoking-ban regulation”. Journal of Development Economics, p. 103-171.

DeCicca, P., Kenkel, D., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2022). “The Economics of Tobacco Regulation: A Comprehensive Review”. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(3), p. 883-970.

WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2021: addressing new and emerging products. Available in https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032095.