What if the delay in the age at which we have children was behind gentrification?

By Ana Moreno-Maldonado and Clara Santamaría

What is Gentrification? It is easy to know when one sees it, but not so easy to define. Let us start with the dictionary definition “A process in which a poor area (as of a city) experiences an influx of middle-class or wealthy people who renovate and rebuild homes and businesses, and which often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents” (Merriam/Webster dictionary).

Beyond the dictionary definition, there is also the personal experience of seeing how a beloved neighborhood changes at neck-brake speed. There are the new shops and restaurants, the hip people walking around… but also the sadness for the loss of iconic places that are closing one by one. The excitement about the fancy coffee shops, the flourishing community garden, and the beautiful bike coop also comes with the worry about the fate of neighbor families who have to move out when the eviction notice arrives.

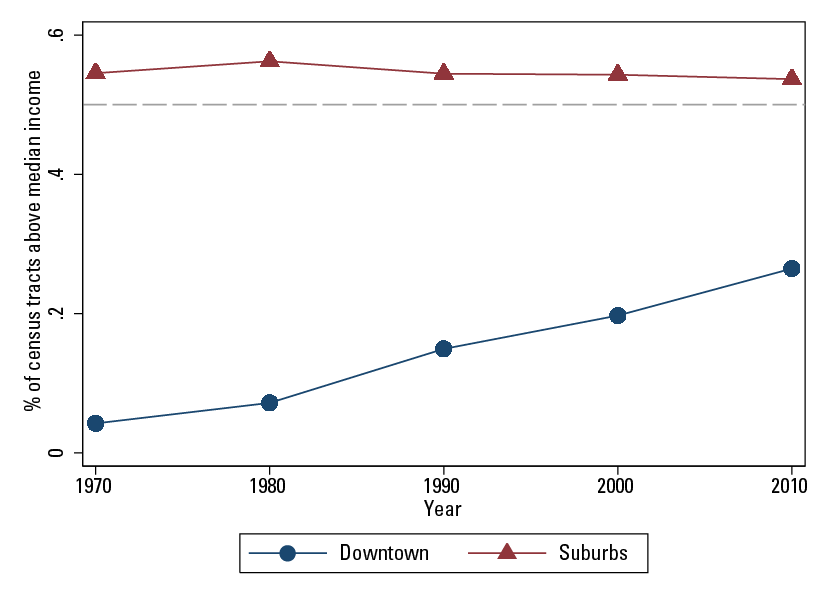

Neighborhoods are always changing; it is part of a city being alive. However, there is a new element in gentrification. The downtown of U.S. cities has experienced an unprecedented transformation in recent decades. As shown in Figure 1, while in 1970 only 5 percent of downtown neighborhoods were high-income (had an average income above the median income of the city), by 2010 this number had grown to 25 percent. This transformation has attracted considerable attention due to its welfare implications for incumbent residents. In particular, the arrival of more educated, higher-income individuals to previously low-income downtown neighborhoods may lead to increases in rent and subsequent displacement of incumbent residents on the one hand, and neighborhood improvements such as reduction in crime or improvement in public goods provision on the other hand.

Figure 1 – Overall gentrification trend

The many causes of gentrification

Before analyzing the welfare consequences of gentrification, it is important to understand its main drivers. The economics literature has found evidence in favor of a variety of causes of gentrification. We can classify the drivers in the literature into three general categories. First, the characteristics of downtown locations have changed in recent decades. For instance, pollution and crime have decreased in downtown locations, and many houses have been renovated (Glaeser, Khan, & Rappaport, 2008; Brueckner & Rosenthal; 2009, Curci & Masera, 2018; Ellen, Horn, & Reed, 2019; Baum-Snow & Hartley, 2020). Second, even if the characteristics of downtown locations has not changed, the valuation of those amenities has. Downtown locations have always implied shorter commutes, but the valuation of those shorter commutes has increased as jobs have increased the income incentive of working longer hours (Edlund et al., 2015; Su, 2021). Third, on top of changes in the characteristics and the valuation of those characteristics, there have also been demographic changes leading to an increase in the number of citizens who value downtown locations the most. In Couture, Gaubert, Handbury, and Hurst (2019), the authors find that the increase in the share of very high-income individuals led to gentrification.

A new potential cause: delay in childbearing

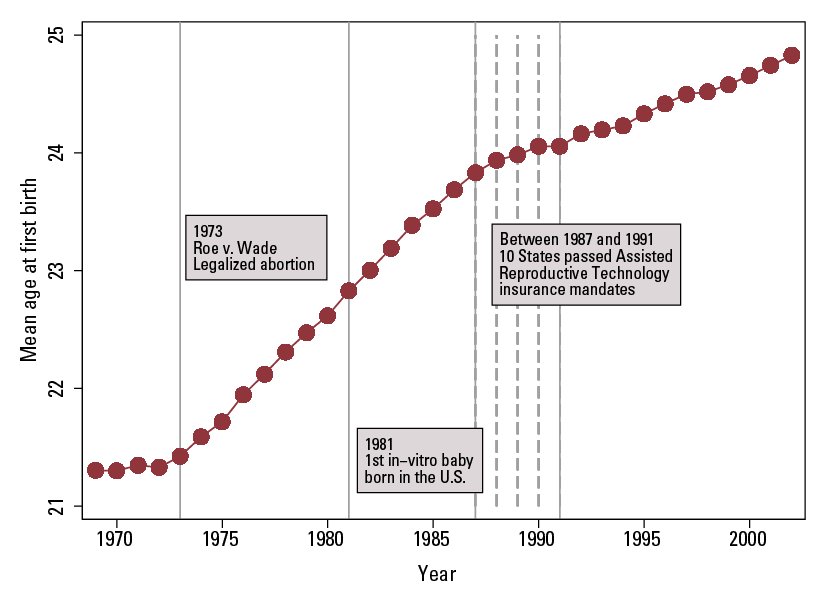

In our recent work, we have quantified the importance of a previously overlooked demographic change behind this phenomenon: the delay in childbearing. The delay in the age of women at first birth has been one of the largest demographic changes in our period of study. Figure 2 plots how the average age of first-time mothers went up from around 21 years old in 1970 to 25 years old by 2010, and this increase was even more pronounced for high-skilled women.

Our motivation for looking at delayed childbearing comes from the observation that location and fertility decisions are tightly linked. Families tend to locate in the suburbs, where houses are larger and schools are of better quality. Meanwhile, young individuals without children tend to locate downtown, where entertainment amenities are high, there are better career opportunities, but houses are small and expensive.

This location pattern of families suggests that, as households have delayed their fertility decisions, there has been an increase in the number of young high-income households who value particularly the downtown of cities. The increase in this group might have increased the overall demand for downtown housing. Even a small initial change can be amplified through rising rents, which leads to sorting on income, and adjustment of endogenous amenities.

Establishing causality

However, it is challenging to prove a causal link going from the delay in childbearing to gentrification. For instance, the correlation could be driven by reverse-causality: as downtown has become more attractive, households may have delayed childbearing to enjoy downtown longer. Moreover, there may be third factors driving both trends.

To address these challenges, we exploit exogenous variation in the incentives to postpone childbearing coming from state-level policies that improved access to infertility treatments. During the 70s, 80s, and early 90s, 12 US states introduced mandates making it compulsory for health insurers to cover infertility diagnosis and treatment. These mandates translated into a substantial reduction of the cost of these otherwise very expensive treatments. As a result of these policies, the use of in-vitro fertilization increased by 1 percentage point (Hamilton & McManus, 2012; Bundorf et al., 2008; Jain et. Al, 2002). However, the effect of the policy went above and beyond the usage effect. Schmidt (2007) finds that white women above 35 increased birth rates by 20%. Moreover, there was not an overall completed fertility effect (Machado and Sanz-de-Galeano, 2015). For instance, Ohinata (2011) finds that women increased the age of first birth by 1 to 2 years. These are quantitatively significant effects.

Exploiting across State and time variation in the introduction of infertility insurance mandates, we run a triple-difference specification which compares census tracts (neighborhoods) in treated cities to those in non-treated cities, before and after the policy, in downtown vs. the suburbs. We find that as a result of the policy, downtown census tracts increased their probability of being above median income by 6.36 percentage points. We also find additional results that support the hypothesis that this increase in income was due to the delay in childbirth. The number of women living downtown increased for the age range 20 to 30 years old, but decreased for the age range 30 to 40 years old.

A counterfactual experiment: what if the delay had not happened?

This empirical strategy delivers the local elasticity of gentrification to the introduction of the policy. However, the change in fertility was much larger and certainly not limited to the introduction of infertility insurance mandates. For instance, female labor force participation and educational attainment increased rapidly over this period, rising the incentives of postponing childbearing beyond improvements in access to infertility treatments. To assess the overall impact of the delay in childbearing on gentrification while considering general equilibrium effects such as the change in housing prices, we propose a model in which households choose both location and fertility timing.

We use individual-level data from the American Community Survey covering from 1980 to 2010 to estimate the model. Using the estimated model, we perform the following counterfactual: how much gentrification we would have observed if the perceived probability of a successful pregnancy after 30 had stayed as it was in 1980. We find that gentrification, measured as the faster growth in income downtown relative to the suburbs, would have been considerably lower in this counterfactual scenario.

Our results highlight that the link between fertility and location choices has important implications for the way we think about gentrification. In particular, we show that the location choices of couples with children are constrained by certain neighborhood characteristics that are difficult to satisfy downtown. This points towards the spatial sorting of individuals not only on income but also on the family type. Moreover, this previously overlooked feature of location choices has consequences that go well beyond neighborhood change. Notably, it also affects local labor markets through commuting times, and ultimately, the career outcomes of females.

Further Reading

“Delayed childbearing and urban revival”

About the authors

Ana Moreno-Maldonado is an Assistant Professor of Economics at CUNEF Universidad. She is a macroeconomist with research interests at the intersection of spatial economics and the economics of the households.

https://sites.google.com/view/ana-moreno-maldonado/

Clara Santamaría is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. She is a macroeconomist with research interests at the intersection of spatial economics, macroeconomics, and labor, with a particular focus on inequality.

https://sites.google.com/view/clarasantamaria/home

References

Baum-Snow, N., & Hartley, D. (2020). Accounting for central neighborhood change, 1980–2010. Journal of urban economics, 117, 103228.

Brueckner, J. K., & Rosenthal, S. S. (2009). Gentrification and neighborhood housing cycles: will America’s future downtowns be rich?. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(4), 725-743.Bundorf, K., Henne, M., & Baker, L. C. (2007). Mandated health insurance benefits and the utilization and outcomes of infertility treatments.

Couture, V., Gaubert, C., Handbury, J., & Hurst, E. (2019). Income growth and the distributional effects of urban spatial sorting (No. w26142). National Bureau of Economic Research.Curci, F., & Masera, F. (2018). Flight from urban blight: lead poisoning, crime and suburbanization.

Edlund, L., Machado, C., & Sviatschi, M. M. (2015). Gentrification and the rising returns to skill (No. w21729). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ellen, I. G., Horn, K. M., & Reed, D. (2019). Has falling crime invited gentrification?. Journal of Housing Economics, 46, 101636.

Glaeser, E. L., Kahn, M. E., & Rappaport, J. (2008). Why do the poor live in cities? The role of public transportation. Journal of urban Economics, 63(1), 1-24.