Or why we should stop doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results

Based on research by Alba Muñoz-Muñoz (UAM) and Hernán D. Seoane (UC3M)

Over the last century, there is an extensive history of applying exchange rate control measures in Latin American economies. These measures, implemented in a context of macroeconomic instability, aim to defend the level of (or accumulate) foreign reserves. Furthermore, there is the implicit reasoning that the government can defend the exchange rate from speculative attacks by maintaining a large level of foreign reserves.

However, why does the country’s government consider exchange rate controls a tool for reserve accumulation?

Exchange rate controls impose limits on the purchase of foreign currency by domestic agents. Often the exchange rate controls also force exporters to sell the proceeds of their exporting activity to the government. In this way, the government purchases currency in a regulated market at a low price while limiting the amount of currency it sells at that price. In this context, it is common that a shadow market for foreign currency emerges, typically at a higher exchange rate. This shadow market is informal and unregulated and the government does not operate in it.

During a monetary crisis, the introduction of exchange controls with the aforementioned characteristics can delay or prevent the outcome of a first-generation currency crisis model, where the monetary authority runs out of reserves while trying to defend the parity. This outcome could cause a significant depreciation of the national currency; see Krugman (1979).

On the other hand, exchange rate controls may hurt the accumulation of foreign reserves due to the economic distortions these restrictions often create and the expectation of abandonment of a policy that cannot be permanent.

Hence, the effectiveness of such controls remains a matter of debate.

We study the case of Argentina, which resorted to these controls from the third quarter of 2011 until December 2015. After the crisis it experienced between 2001 and 2002, Argentina’s economy started to grow in a very favorable international context, allowing the economy to achieve sovereign and external surpluses until 2010. At the beginning of 2011, Argentina showed strong signs of stagnation, an increasing loss of foreign reserves, and twin deficits, in both the fiscal and current accounts.

Capital control measures accelerated as the economy was deteriorating and the exchange rate appreciated in real terms. By mid-2011, there was a significant deterioration in exports and a fall in imports at a slower rate, related to the lack of macroeconomic growth and an increase in capital outflows. The government introduced the first exchange rate controls, commonly known as the “cepo cambiario”.

In Muñoz-Muñoz and Seoane (2024), we examine the impact of exchange rate control on the accumulation of foreign reserves using the Synthetic Control Method (SCM) developed by Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003). We use the introduction of the “cepo cambiario” in Argentina in the third quarter of 2011 as a natural experiment. We construct a synthetic Argentina without the controls and compare it to Argentina. We use data from 36 countries -including emerging and developed countries- from 2002 to 2017. This allows us to study the effects of the first implementation of exchange controls and their abandonment in 2015. The model includes several predictors, such as lags of accumulation of reserves, the current account, M2, the nominal exchange rate, the terms of trade, and the primary deficit.

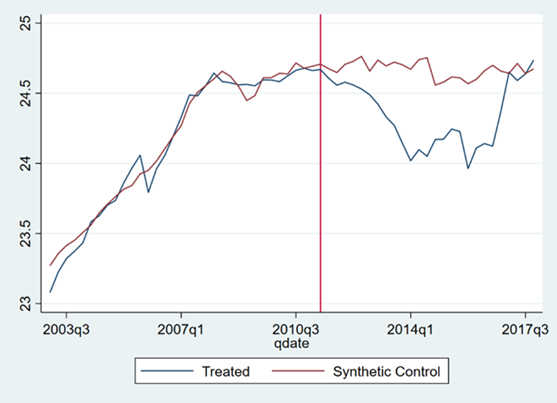

Figure 1: Foreign reserves in Argentina and the counterfactual

Note: The vertical axis measures the foreign reserves of Argentina (blue) and Synthetic Argentina (red) in natural logarithms. The red vertical line indicates the introduction of exchange rate controls in 2011Q3.

Figure 1 plots Argentina (treated) and the counterfactual Argentina (Synthetic Control unit with positive weights in the baseline for Ecuador, Hong Kong, Norway, Perú, Russia, and the UK). The pre-intervention trends for the synthetic control and Argentina align closely until the third quarter of 2011. After the intervention, the evolution of the log of the foreign reserves from Argentina dropped compared to the counterfactual. By our estimates, the counterfactual economy indicates that the introduction of the exchange rate control reduced the log foreign reserves by 20% by the first quarter of 2014.

It is frequently argued that this type of control is introduced to maintain or even increase the level of external reserves. However, as the figure indicates, the set of exchange rate interventions introduced in Argentina produced the opposite effect, suggesting that the exchange rate controls harm the foreign reserves.

We hypothesize two possible channels in which exchange rate controls may have had this adverse effect. First, there are limits to the government’s ability to purchase foreign reserves because the private sector, in anticipation of a depreciation of the currency, prefers to hold foreign currency rather than sell it to the government. Moreover, as the private sector anticipates a depreciation of the currency, they demand foreign currency in order to anticipate imports and anticipate the payments of dollarized debt. As a result, the increased private sector demand competes with the government’s need for foreign currency purchased at the official exchange rate.

Our main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

We find that controlling the exchange rates causes the country’s foreign reserves to fall. In Argentina, the government did not achieve its intended goal of protecting foreign reserves, which instead fell by 40% relative to the counterfactual economy without the intervention.

Moreover, by the end of 2015, Argentina removed these restrictions, which affected the market value of the foreign currency and the expectations of its future price. Our results show that, within a year of the abandonment of these controls, the accumulation of foreign reserves reached up with the counterfactual economy.

Further Reading:

Abadie, Alberto, and Javier Gardeazabal. “The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the Basque Country.” American economic review 93.1 (2003): 113-132.

Krugman, Paul. “A model of balance-of-payments crises.” Journal of money, credit and banking 11.3 (1979): 311-325.

Muñoz-Muñoz, Alba and Seoane, Hernán D., “Exchange rate controls and foreign reserves”. Mimeograph (2024), available here

About the authors:

-

Alba Muñoz-Muñoz is a student at the Master in Quantitative Economic Analysis at the UAM.

-

Hernán D. Seoane is Profesor Titular de Economía at the UC3M. web