How do Central Bank Asset Purchases work in theory and how do they affect fiscal policy and inflation?

By Carlo Galli

Based on research by Gaetano Gaballo and Carlo Galli.

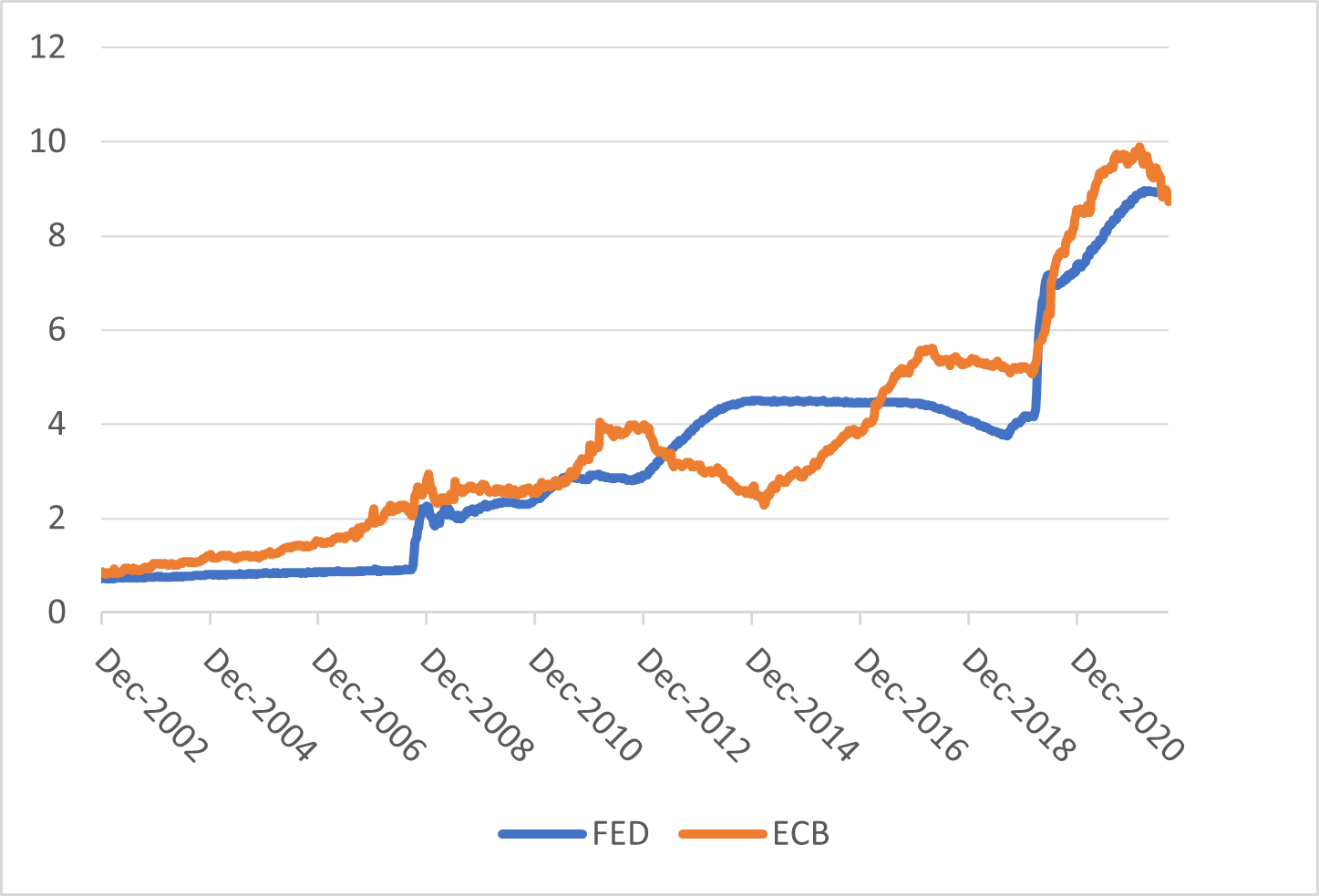

The most striking change in the conduct of monetary policy in the last two decades is certainly the permanent implementation of large-scale asset purchases (APs henceforth), also known as Quantitative Easing. By now, this non-conventional policy has been adopted by many developed and emerging countries and has brought central bank balance sheets to grow to unprecedented levels, as illustrated in Figure 1 for the case of the US and the Euro Area.

Figure 1: Central Bank Total Assets, in trillion US dollars.

The role of Asset Purchases and their effects

Most central banks introduced APs to overcome the limits of the zero lower bound on their conventional policy instrument (that is, short-term rates) by exerting downward pressure on long-term government bond yields. APs soon took a macroprudential role too, offering a buffer to the sovereign bond market, hedging sudden shocks and the resulting large price fluctuations. In the Eurozone, sovereign bond purchases have been advocated as a powerful policy to fight financial fragmentation in sovereign debt markets and protect countries against speculative attacks.

The growing practical importance of APs has posed a number of questions, both empirical and theoretical. First, do these policies actually work in practice? There is ample empirical evidence that they do have an effect. The most convincing evidence shows that the effects are mostly “narrow”, or local, in the sense that most of the impact is in the assets that are directly targeted by the policy. Some works study the broader macroeconomic effects of APs, but we know much less about this dimension, and the existing evidence is less compelling.

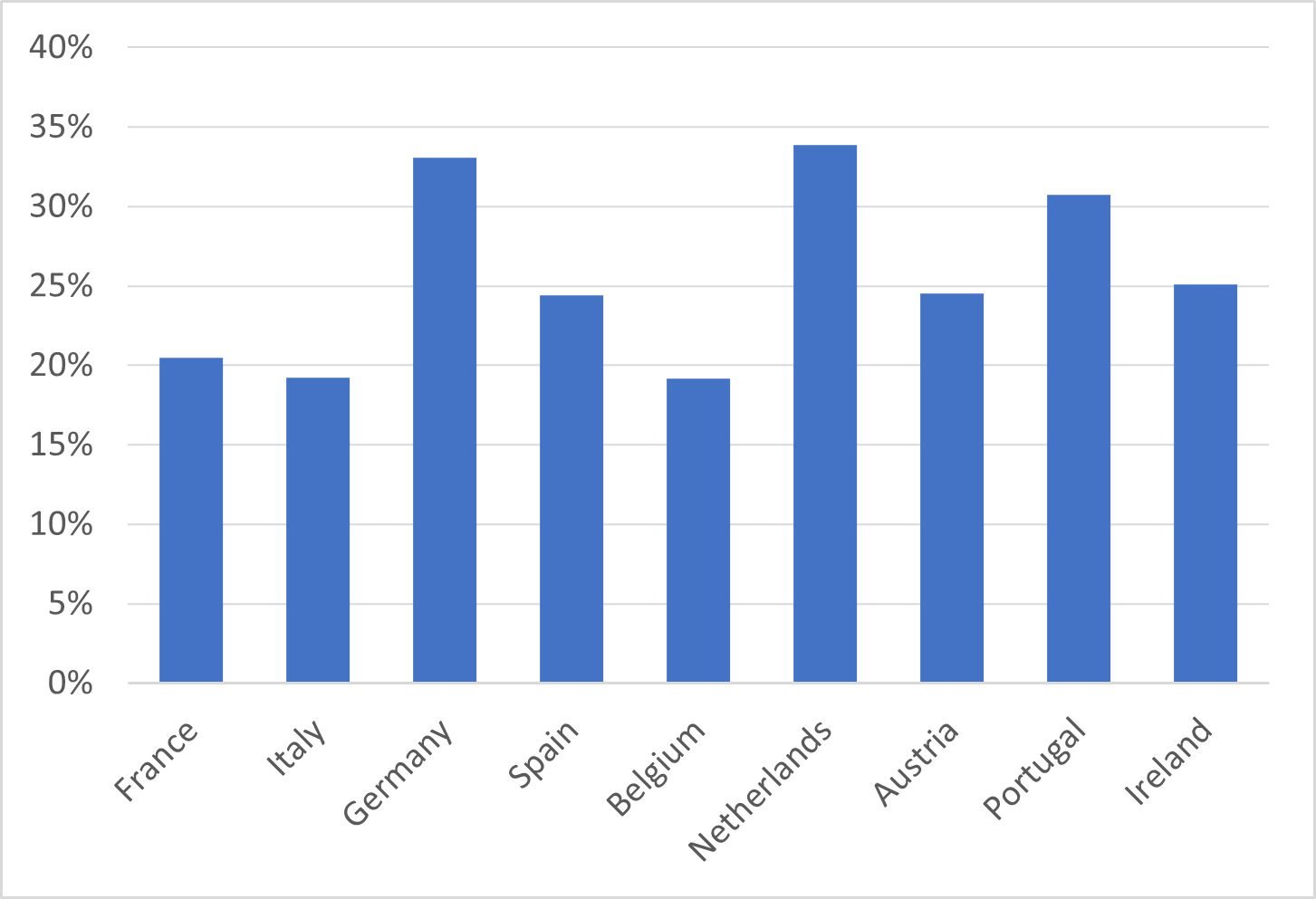

A second, increasingly important question concerns the consequences, for monetary policy and the macroeconomy, of the large increase in the size and the number of different financial risks contained in central bank balance sheets. A version of this question, particularly relevant for the Eurozone, is what the consequences of a sovereign default for the ECB would be, considering the sheer size of its current sovereign debt holdings (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Share of general government debt purchased by the ECB. The data is as of Q1 2022 and considers only the Public Sector Purchase Program.

How do Asset Purchases work in theory?

As bluntly put by Fed president Ben Bernanke in a famous speech, “the problem with quantitative easing is that it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory”. That is, while there do exist models that describe the channels through which APs have either narrow effects on asset prices or broader effects on the real economy, our understanding of the mechanisms at work is still quite limited.

In our ongoing work, we provide a new rationale for how APs may work in theory and what are its consequences on inflation, fiscal policy and welfare. Our theory nests a model of financial market trading with noisy dispersed information à la Hellwig, Mukherji and Tsyvinski (2006) within a stylised model of fiscal-monetary policy. In a nutshell, we model the interaction between a government that issues nominal defaultable debt, a central bank that may issue money to households in order to buy such debt, and a household sector that holds bonds, money and consumes.

We make two important yet realistic assumptions. First, there exist bond market imperfections in the form of limits to arbitrage: agents face bounds in the bond positions they can take. Second, there are information frictions in the form of heterogeneous beliefs on the probability that the government may default. With this simple model at hand, we can examine the effects of APs on sovereign yields, and in turn on public finances, as well as the consequences of sovereign default on the central bank balance sheet and eventually on inflation.

First, we show that APs do have a narrow effect on asset prices due to the presence of financial market imperfections. The effect is larger, the stronger these imperfections. Because investors have heterogeneous beliefs on the value of government bonds, APs have a positive effect on asset prices because they crowd out a specific part of the investor distribution, that is, those investors who are “pessimists” and have a low willingness to buy. At the same time, APs have a negative effect because they make the information contained in bond prices more precise in bad states of the world, forcing the government to pay higher interest on its debt.

Second, we consider the macroeconomic consequences of APs. The effect on asset prices passes through directly to the cost of government funding: insofar as APs lower sovereign interest rates, default is less likely and the government has a lower need to raise taxes. At the same time, we show that APs expose the central bank to the risk of large losses in case the government defaults on its debt. In the absence of fiscal transfers from the government, central bank losses on the asset side must correspond to a drop in the value of liabilities, i.e., money, and therefore inflation. Large APs thus tie inflation to default risk, making it more difficult for the central bank to fulfil its price stability mandate.

We characterise the net impact of APs in light of these trade-offs. We show optimal APs are non-zero but bounded, and their effectiveness and optimal size are contingent on the fundamentals of the economy. In sum, APs have more bite if sovereign debt crises are deeper or more likely.

References:

Bernanke, Ben. S., “A Conversation: The Fed Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/20140116_bernanke_remarks_transcript.pdf, January 16th, 2014. Q & A at the Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

Hellwig, Christian, Arijit Mukherji, and Aleh Tsyvinski. 2006. “Self-Fulfilling Currency Crises: The Role of Interest Rates.” American Economic Review, 96 (5): 1769-1787.

Krishnamurthy, Arvind, “QE: what have we learned?”, https://bcf.princeton.edu/events/arvind-krishnamurthy-on-qe-what-have-we-learned/, March 24th, 2022. Markus’ Academy lecture.

About the authors:

Gaetano Gaballo is an Associate Professor at HEC Paris. He works on macroeconomic theory, information and monetary economics.

https://www.mwpweb.eu/gaetanogaballo

Carlo Galli is an Assistant Professor at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. He is interested in macroeconomics, international finance and information economics.

Further Reading:

Gaballo, Gaetano and Carlo Galli, 2022. “Asset Purchases and Default-Inflation Risks in Noisy Financial Markets”, working paper.