Refugees fleeing conflict justify the need for coordination at a supranational level

By Jesús Fernández-Huertas Moraga.

Based on research by Simone Bertoli, Herbert Brücker, and Jesús Fernández-Huertas Moraga.

The European Union received more than 3 million applications for asylum between 2014 and 2016. The response of European countries was diverse. Some erected fences while others, notably Germany, increased their processing efforts to meet the arrival of new refugees, 27 percent of whom were fleeing the war in Syria. Germany received 43 percent of asylum applications. In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. The EU unified its response and invoked for the first time its Temporary Protection Directive, approved in 2001, to react to emergency situations. By December 2022, UNHCR estimated that close to 5 million Ukrainians had received temporary protection in some European country, 32 percent of whom chose neighboring Poland and 21 percent Germany. In situations like these, it can be crucial to understand to what extent the policies of destination countries affect the choice of prospective refugees about where to settle and potentially apply for asylum. If these policies do in fact affect choices, it can be justified to coordinate them in order to avoid negative externalities, for example, within the European Union.

Asylum seekers face more uncertainty than other immigrants

When deciding where to live, an individual will typically evaluate whether her welfare will be higher in one location than another. This will determine if she stays at home or becomes an immigrant, and if so, where she goes as an immigrant. In the case of people fleeing a conflict, they face a similar problem but with important differences. First, they may not have the option of staying at home. Second, their ability to reach different destinations may be affected by asylum policies, policies that are specifically designed to either attract or deflect asylum seekers and that generate additional uncertainty in their decisions.

The effect of asylum policies on applications is difficult to discern because these policies are very diverse and thus hard to commonly codify and compare across countries. In Bertoli et al. (2022), we focus on three common policy outcomes that are associated with countries’ asylum policies and then assess how these policy outcomes relate to asylum flows:

- Recognition rates. This is the probability that an asylum application is accepted and an asylum seeker is recognized as a proper refugee. It was 28 percent on average in the European Union between 2009 and 2017.

- Processing times. This is the average time it takes to decide on an asylum application. It was 9.5 months on average between 2009 and 2017.

- Repatriation rates. It is the probability that a rejected asylum applicant is sent back to its origin in a particular destination country. We build a proxy for this variable by dividing different measures of repatriations by the total number of negative decisions by country of origin and destination.

A contribution of our work (Bertoli et al., 2022) is that we manage to build comparable series for these three measures that vary at the country of origin, country of destination, and time levels. We then proceed to document the sources of variations on these measures, which jointly reflect the uncertainty that asylum seekers face by country of destination. We find that more than half of the variation in recognition rates is explained by origin factors. In a sense, these are good news for the international refugee system, according to which all of the variation in recognition rates across countries should be origin-specific. All European Union countries are signatories of the Geneva Convention of Refugees, which states that refugee cases should be studied on their merits, and these merits should be dictated by the conditions at the origin, that is, whether there is a well-founded fear of persecution for the asylum seeker.

On the other hand, processing times are a more discretionary element of asylum policy at the disposal of governments. We find that more than half of the variation in processing times across origins and destinations in Europe is explained by destination-specific factors.

Relationship between asylum applications and flows

In theory, we should expect that recognition rates and asylum applications would be positively associated, as higher recognition rates would attract more asylum flows. This has been documented in different datasets, such as Hatton (2009). However, we only find a positive correlation between recognition rates and asylum flows after we control for repatriation rates and the interaction between recognition rates and processing times.

In principle, higher processing times should discourage applications for asylum, as they imply more uncertainty for asylum seekers and a period over which most countries do not allow asylum seekers to work, for example. We know that employment bans do have a negative effect on outcomes even for accepted refugees (Fasani et al., 2021). Still, there are some asylum applicants for whom higher processing times could be good news. In particular; this is the case if their recognition rates are low because the time they are waiting for a decision is a time during which they will not be deported, and they can stay legally in their destination country.

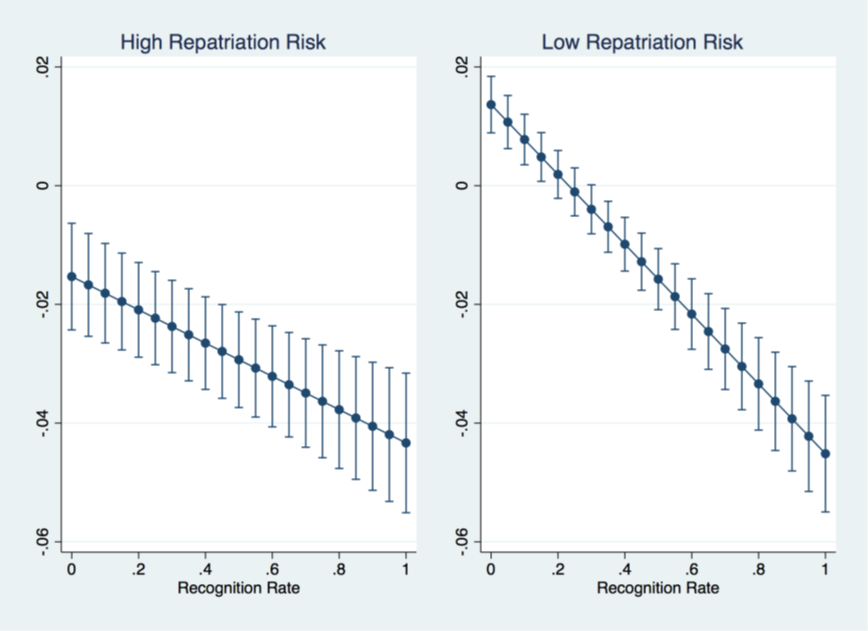

This is what Figure 1 documents. First, we can observe that the negative effect of processing times on asylum applications becomes larger as the recognition rate increases. Second, we show that some countries are characterized by low repatriation risks and recognition rates below 17 percent, where increases in processing times were associated with increases in asylum applications. Our interpretation is that when chances of being granted refugee status are low and the risk of repatriation is also moderate, lodging an asylum application becomes a (temporary) legal migration scheme.

Figure 1: Marginal Effect of Processing Times on the Share of Asylum Applications

In order to gauge the quantitative relevance of these correlations, we perform some simple simulations where we use the actual changes in processing times that were recorded in the different recipient countries between January 2014 and the peak of the refugee crisis in October 2015. German efforts to expand their processing capacity were correlated with a significant increase in applications from origins with high recognition rates, such as Syria, for whom processing times decreased from 8 to 4 months. They were mostly diverted away from Sweden, where Syrians had to wait 3 months in January 2014 and 10 months on average in October 2015. For Syrians, the observed variations in processing times increased applications in Germany by 16.1 percent, and led to a 35.3 percent reduction in Sweden.

Causality: safe countries of origin

The above analysis takes advantage of correlations in equilibrium outcomes, which could only be interpreted with the help of a model that differentiates the demand for and the supply of asylum. This is why we refer to recognition rates, processing times, and repatriation risks as policy outcomes. To establish a causal effect of policies, we need to focus on a particular one that is sufficiently common across destinations. We study the inclusion of an origin in a list of safe countries of origin in different destinations at different points in time. This inclusion implies that asylum applicants from these origins can see their application directly rejected.

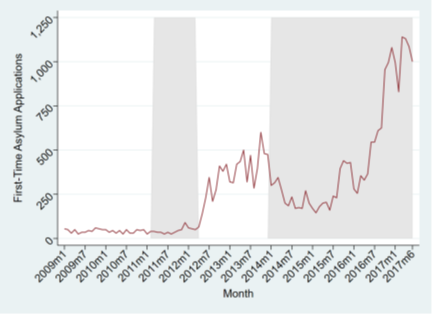

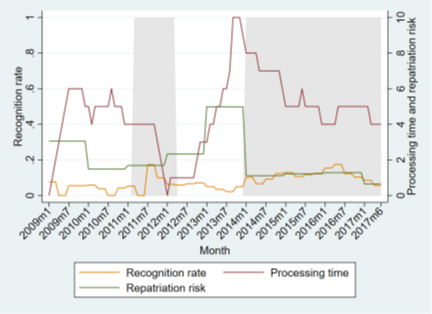

Figure 2 reflects the type of variation that we exploit with the example of Albanian asylum applications to France.

Figure 2: Evolution of Albanian First-Time Asylum Applications in France and Policy Measures by inclusion in the list of Safe Countries of Origin

Notes: Shaded areas represent the time during which Albania was in the French list of Safe Countries of Origin.

Albania was considered a safe origin by France twice during this period, first in 2011 and then again in 2014. Both inclusions coincided with notable reductions in processing times, while the 2012-2013 period when Albania was out of the list saw both an increase in asylum applications of Albanians in France and an increase in processing times.

More generally, we use the generalized differences-in-differences estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille (2022), which allows for a non-staggered design, with units going in and out of treatment status (safe countries of origins lists in our case), as in Figure 2. We show that the inclusion in such lists significantly decreased asylum applications from a particular origin by around 50 percent after 11 months. We also show that the inclusion in the list was associated with reductions of around 2 months in processing times, which took place about 9 months after the policy change.

About the authors:

Simone Bertoli is Professor of Economics at CERDI, Université Clermont Auvergne. His main research interests include international migration, economic development, and labor economics.

https://www.iza.org/person/6015/simone-bertoli

Herbert Brücker is Professor of Economics at Humboldt University Berlin. He works on international migration, labor markets, European integration, and applied quantitative methods.

https://www.bim.hu-berlin.de/en/ppl/chairs/bruecker/bruecker-anriss

Jesús Fernández-Huertas Moraga is an Associate Professor at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. His main research interests include international migration, economic development, and labor economics.

https://sites.google.com/site/jfmecon/

Further Reading:

Bertoli, S., Brücker, H., & Fernández-Huertas Moraga, J. (2022). Do applications respond to changes in asylum policies in European countries? Regional Science and Urban Economics, 93, 103771, 1-17.

References:

de Chaisemartin, C. & D’Haultfoeuille, X. (2022). Difference-in-Differences Estimators of Intertemporal Treatment Effects. NBER Working Paper Series, 29873.

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., & Minale, L. (2021). Lift the Ban? Initial Employment Restrictions and Refugee Labour Market Outcomes. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(5), 2803-2854.

Hatton, T. (2009). The Rise and Fall of Asylum: What Happened and Why? Economic Journal, 119, 183–213.