Estimating the effect of milk inspections on urban mortality, 1880-1910

By Daniel Rees

Based on research by D. Mark Anderson, Kerwin Kofi Charles, Michael McKelligott, and Daniel I. Rees

Economists have a longstanding interest in government-mandated quality inspections (Mill 1859; Jevons 1882). Viewed as remedying market failure caused by asymmetric information between buyers and sellers, government inspections incentivize adherence to minimum quality standards (MQSs) but, in theory, can restrict output and “price out” economically vulnerable consumers.

Many goods and services are subject to MQSs and government inspections. For instance, restaurants in the United States are periodically inspected by local, county, or state health departments, while meat and poultry shipped across state lines must be inspected by the Food Safety and Inspection Service. Although quality inspections are, in the words of Jevons (1882, p. 44), supposed to offer protection against the unwitting purchase of “putrid sausages, poisonous pickles, [and] dangerous guns,” previous research has often focused on code violations or inspection scores, neither of which is necessarily related to consumer health or safety.

In recent work (Anderson et al. 2022), we examine the effects of milk inspections, which were undertaken by most major American cities in the 1880s and 1890s, on two health-related outcomes of obvious importance to consumers: infant mortality and mortality from waterborne and foodborne diseases (hereafter referred to as “waterborne diseases”). Before the advent of milk inspections, the milk supply of American cities was regularly diluted with (potentially contaminated) water and skimmed; boric acid was often added as a preservative (Meckel 1990). Although consumers occasionally complained about the use of boric acid, public health experts were particularly concerned about dilution and skimming, both of which reduced the nutritional value of milk. In an effort to curb these practices, municipal inspectors were tasked with collecting and analyzing milk samples. Dairymen, dealers, and retailers who were caught peddling substandard milk were fined, and their product was spilled onto the ground.

Milk in the last decades of the 19th century can be thought of as an “experience” or “credence” good. Buyers cannot determine the quality of an experience good before its purchase, while the quality of credence goods is difficult to evaluate even after purchase and consumption. Milk inspectors, with the help of a lactometer, measured the percentage of solids in milk to determine whether it was watered or skimmed. Consumers, on the other hand, could not easily ascertain the quality of milk because caramel, dyes, salt, and sugar were added to restore its color, body, and taste. If an infant or child ingested milk to which contaminated water had been added, linking an infection back to its original source would have been impractical, if not impossible.

Today, health and safety regulations are typically complex and multi-layered, making it challenging to credibly estimate the effect of any one facet of the regulatory environment. By contrast, urban milk markets were wholly unregulated before the hiring of municipal inspectors. Requirements that milk meet bacteriological standards, which encouraged pasteurization and requirements that dairy cows be tested for tuberculosis were post-1900 phenomena. Moreover, the supply chain was, by modern standards, exceedingly short and simple. The milk was transported from nearby farms on wagons or trains in the morning and then sold—and typically consumed—within a day or two.

Contemporary public health experts credited milk inspections with saving the lives of thousands of infants and children every year. According to Dr. H.A. Pooler, milk inspections in New York City “had a very happy effect by reducing the death rate of children…3,673 less in 1883 than in 1882, other conditions of the city being about the same” (Morris 1885, p. 250). Dr. Pooler did not adjust his estimate for the fact that mortality had begun to trend downwards in New York City (and other major American cities) well before the hiring of milk inspectors, but his claim of ceteris paribus was not otherwise farfetched. Milk inspections were the first—and, for almost two decades, the only—concerted, widespread effort aimed at improving the quality of the milk supply and reducing the alarmingly high mortality rates among infants and children living in the crowded tenements of major U.S. cities (Meckel 1990).

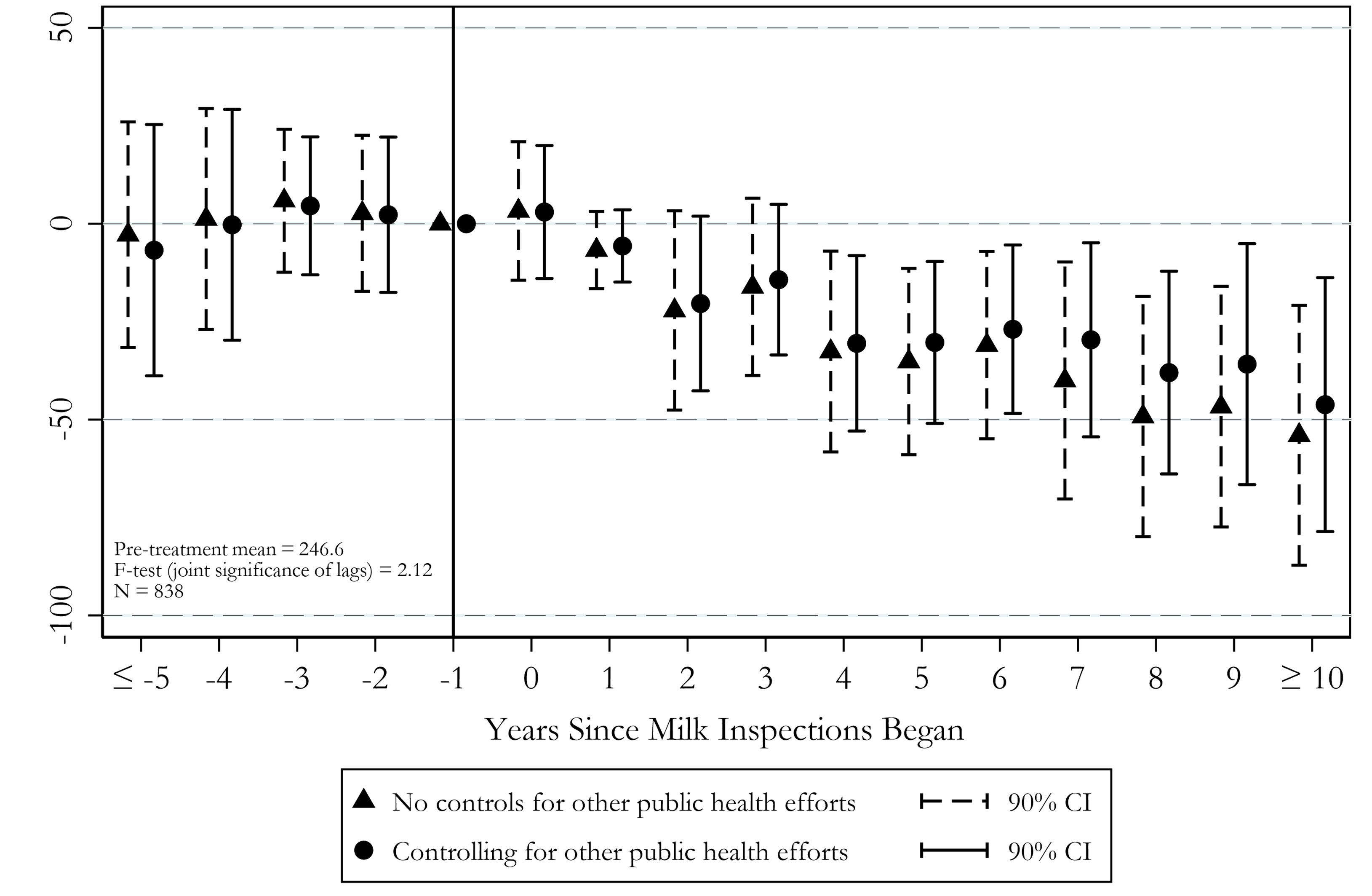

Milk inspectors were tasked with enforcing a minimum threshold for milk solids (fat, carbohydrates, and minerals), typically set at 12 percent. Using newly transcribed mortality data from 35 U.S. cities for the period 1880-1910, we find little support for the hypothesis that enforcing this well-defined MQS through pre-market inspections reduced infant mortality. By contrast, when we shift our focus to waterborne diseases such as diarrhea and typhoid, there is strong evidence that enforcing an MQS through inspections led to better health outcomes. Five years after their start, milk inspections are associated with a 12 percent reduction in mortality from waterborne diseases; after 10+ years, inspections are associated with a 19 percent reduction in mortality from waterborne diseases (Figure 1). Inspections likely reduced waterborne mortality by discouraging dairymen, dealers, and retailors from diluting their milk with water, which was all too often demonstrably contaminated with typhoid or other potentially harmful bacteria such as E. coli. However, because many typhoid outbreaks at the turn of the 20th century were linked to the handling of milk by infected dairy workers, we cannot dismiss the possibility that inspections reduced waterborne mortality through curbing the sale of skimmed milk.

Figure 1: The Effect of Milk Inspections on Waterborne Mortality, 1880-1910

Notes: Based on annual data from municipal and state public health reports (1880-1899) and Mortality Statistics (1900-1910). Two-way fixed effects estimates (and their 90% confidence intervals) are reported, where the omitted category is one year before treatment. The dependent variable is equal to the number of deaths related to waterborne diseases per 100,000 population in city c and year t. All models control for city and year-fixed effects. Other public health efforts are described by Anderson et al. (2022). Estimates are weighted by city population, and standard errors are corrected for clustering at the city level.

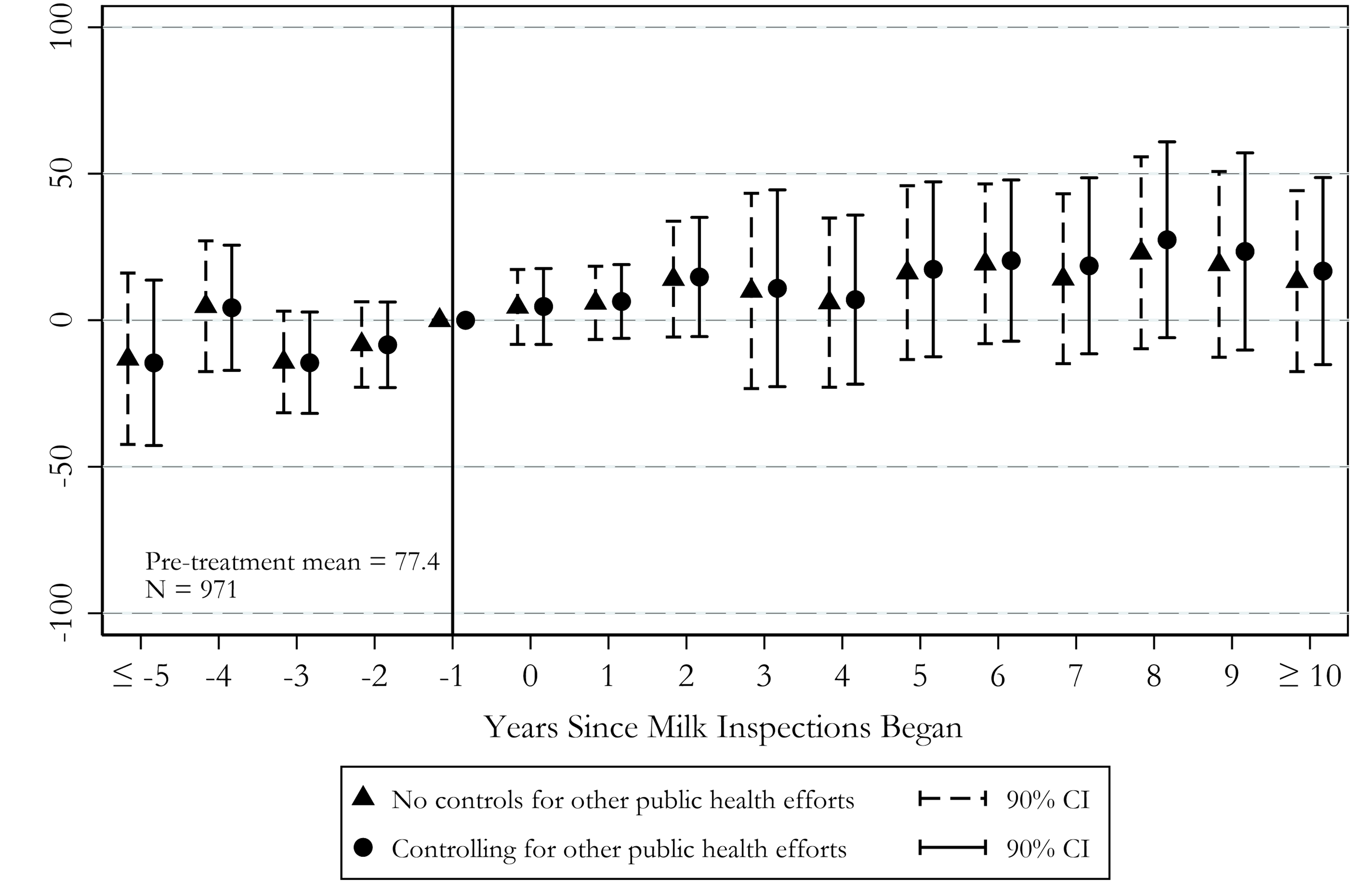

By the 1880s, physicians were recommending that milk be heated at home to destroy microscopic pathogens, and it is possible that the public discourse surrounding the hiring of milk inspectors encouraged this practice. To explore whether household efforts to sterilize milk can explain the negative association between milk inspections and waterborne mortality, we turn to diphtheria mortality. Diphtheria can be transmitted through the consumption of raw dairy products but not through water; the bacteria that cause diphtheria are easily destroyed by heating. We find no evidence that milk inspections reduced diphtheria mortality (Figure 2), suggesting that the strong, negative association between milk inspections and mortality from waterborne diseases is not driven by household efforts to sterilize milk through heating.

Figure 2: The Effect of Milk Inspections on Diphtheria Mortality, 1880-1910

Notes: Based on annual data from municipal and state public health reports (1880-1899) and Mortality Statistics (1900-1910). Two-way fixed effects estimates (and their 90% confidence intervals) are reported, where the omitted category is one year before treatment. The dependent variable is equal to the number of diphtheria deaths per 100,000 population in city c and year t. All models control for city and year-fixed effects. Other public health efforts are described by Anderson et al. (2022). Estimates are weighted by city population, and standard errors are corrected for clustering at the city level.

Our results are directly relevant to ongoing policy debates regarding MQSs and their effects on consumer welfare. Because they restrict output and raise prices, MQSs clearly benefit producers at the expense of consumers provided that quality can be accurately assessed before purchase (Bockstael 1984). There is, however, a stronger theoretical case to be made for MQSs if quality cannot be easily assessed before or even after purchase (Leland 1979). A handful of previous studies provide evidence that, when applied to production inputs, MQSs restrict supply and put upward pressure on prices. Our study is the first to provide evidence that MQSs can improve consumer health when applied directly to an experience or credence good.

References:

Bockstael, Nancy E. 1984. “The Welfare Implications of Minimum Quality Standards.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 66(4): 466-471.

Jevons, William Stanley. 1882. The State in Relation to Labour. New York, NY: Macmillan and Company.

Leland, Hayne E. 1979. “Quacks, Lemons, and Licensing: A Theory of Minimum Quality Standards.” Journal of Political Economy, 87(6): 1328-1346.

Meckel, Richard. 1990. Saving the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850-1929. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mill, John Stuart. 1859. On Liberty. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Morris, J. Cheston. 1885. “The Milk-Supply of Our Large Cities: The Extent of Adulteration and Its Consequences: Methods of Prevention” Public Health, Papers and Reports, 10: 246-252.

About the authors:

Mark Anderson is a Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics, Montana State University.

https://www.montana.edu/econ/directory/1523860/dmark-anderson

Kerwin Kofi Charles is a Professor of Economics, Policy, and Management at the Yale School of Management.

https://faculty.som.yale.edu/kerwincharles/

Michael McKelligott is a Ph.D. candidate at the Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago.

https://harris.uchicago.edu/directory/michael-mckelligott

Daniel I. Rees is a Professor in the Department of Economics, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

http://economics.uc3m.es/personal/rees/

Further Reading:

Anderson, D. Mark, Kerwin Kofi Charles, Michael McKelligott, and Daniel I. Rees. 2022. “Safeguarding Consumers Through Minimum Quality Standards: Milk Inspections and Urban Mortality, 1880-1910.” NBER WP No. 30063.