Why do countries with a worse rule of law experience greater volatility and inequality?

By Martin Dumav and William Fuchs

Based on research by Martin Dumav, William Fuchs, and Jangwoo Lee.

Many, if not most, economic interactions are carried out with very incomplete or no formal contracts at all. In the shadow of weak contract enforcement institutions, people often rely on the repeated nature of their interactions to establish relational or self-enforcing contracts. However, such reliance on relational contracts may not provide the same degree of trust as a strong rule of law can provide. In our recent paper (Dumav, Fuchs, and Lee, 2022), we develop a parsimonious model of relational contracts that help rationalize empirical evidence showing that countries with better rule of law – where courts are more easily enforce contracts—experience less economic volatility, have less productivity dispersion amongst its firms and lower wage inequality.

Rule of law and economic outcomes

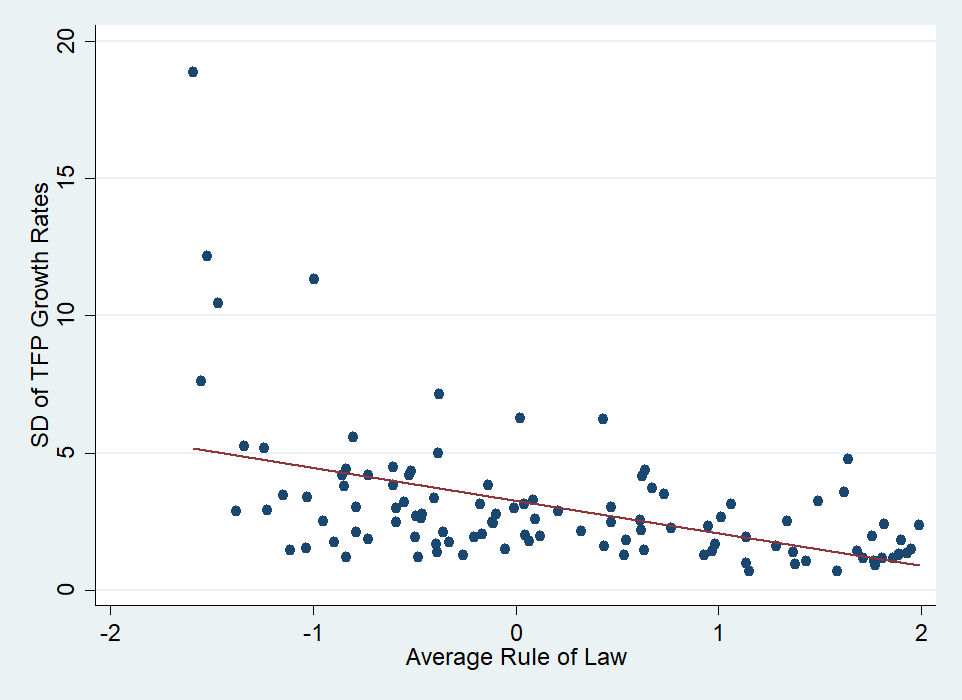

We document empirical evidence that countries with a worse rule of law, as measured by the World Bank (in particular, World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) database), have greater volatility in their growth rates and in their economy overall. This is the case for countries like China, India, and Russia, which rely more on relational contracts based mostly on trust between two parties. Countries with better rule of law, however, like the U.S., the U.K., and Australia, see overall less economic volatility. We find that a one point decrease (in a scale of 5) in the rule of law measure is associated with a reduction in aggregate volatility by 1.2 percentage points. This represents a 35% decrease, since the average level of aggregate volatility is around 3% in the sample, as Figure 1 below shows.

Figure 1 – Rule of Law and Volatility in Growth Rates

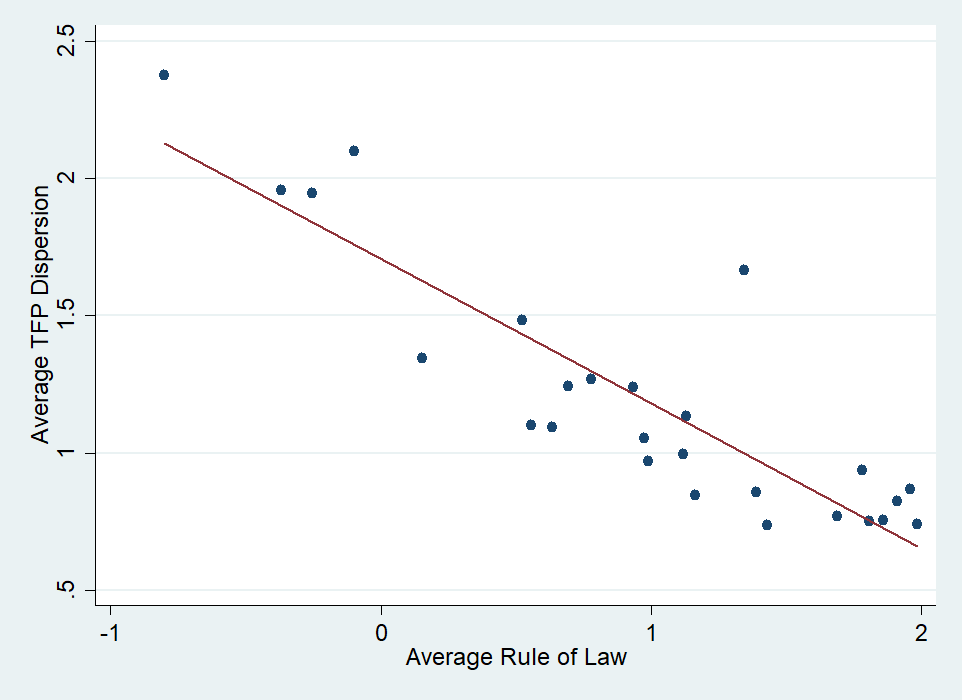

The second finding suggests that India and China could potentially reduce the ratio of productivities of the most productive to least productive firms by roughly 60% if they could improve the quality of their legal system to that of the United States. This evidence is summarized in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – Rule of Law and Productivity Dispersion

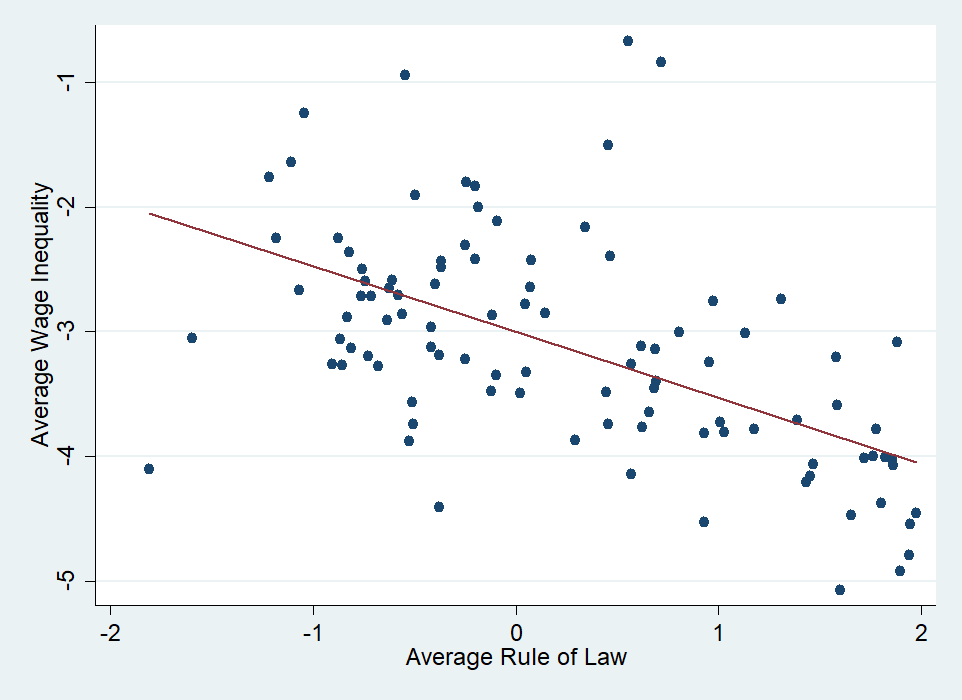

Finally, we also find a negative relationship between the rule of law measure and wage inequality.

Figure 3 – Rule of Law and Wage Inequality

All three findings are consistent with their main theorem: countries with poor contractual environments experience greater aggregate volatility, productivity dispersion and wage inequality.

In other words, in countries with a weaker legal system, workers in less productive businesses are quicker to stop putting in effort during rocky economic times. If India and China were to strengthen their legal systems, the productivity gap between the countries’ top and bottom companies could shrink.

Self-enforcing contracts, Morale effect, and Aggregate Shock Amplifications

To rationalize these empirical relationships between the country’s quality of contract enforcement institutions and economic outcomes, we offer a model of relational contracting. We show that a very tractable model of relational contracts can simultaneously explain both micro and macro phenomena.

We compare two theoretical economic environments, one with good rule of law, or contract enforcement, and the other marked by poor enforcement. Our analysis shows that, when contract enforcement is poor, employee morale suffers, ultimately sparking more economic volatility and greater differences in productivity across companies. Employees don’t see promises as credible.

Our model features two main building blocks. The first assumption is that firms are hit by shocks that make them more or less profitable. Importantly, these shocks are persistent, in that bad or good times are likely to stay.

The second key ingredient is that when coping with uncertainty, contracts might not be perfectly enforceable, depending on the legal environment. This lack of contract enforcement can tempt a person to renege on a promise. When an employer reneges, however, there is a cost: the business relationship is damaged.

Our model highlights the role of persistence in productivity during bad times. When the current state is bad, the future value from maintaining the relationship is low, and the principal cannot credibly promise to make large payments. Thus, in bad times, the firm cannot motivate the agent to exert high effort. Consistently with the empirical evidence, this “low morale effect” in turn amplifies the adverse effect of uncertainty in productivity. This amplification effect also sheds light on wage inequality in countries with limited legal enforcement.

Building Trust

These findings have implications not only for the employer-employee relationship, but also for relationships between two businesses, and for governments across the globe. The economic cycle could be smoother if countries had better rule of law.

For employers, the model confirms that in difficult economic times, it is tough to motivate workers, and companies risk a significant drop in productivity. But employee trust mitigates that drop. Building trust is even more important for businesses in countries where the rule of law is weak and relational contracts are the norm.

About the authors:

Martin Dumav is an Associate Professor of Economics at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. He is a microeconomist with applied interests in behavioral economics, contract design,and political economy.

https://sites.google.com/site/mdumav/

William Fuchs is a Full Professor at UT Austin McCombs School of Business, and is a distinguished research visitor at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. His research interests cover finance, game theory, contract theory, and macroeconomics.

https://sites.google.com/site/wfuchs/

Jangwoo Lee is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research interests primarily focus on dynamic games and their applications to corporate finance.

https://sites.google.com/view/jangwoolee/home

Further Reading:

Dumav, Fuchs, and Lee (2022) “Self-enforcing contracts with persistence” May 2022 Journal of Monetary Economics.