How do interest groups walk their way through electoral politics?

Based on research by Álvaro Delgado Vega.

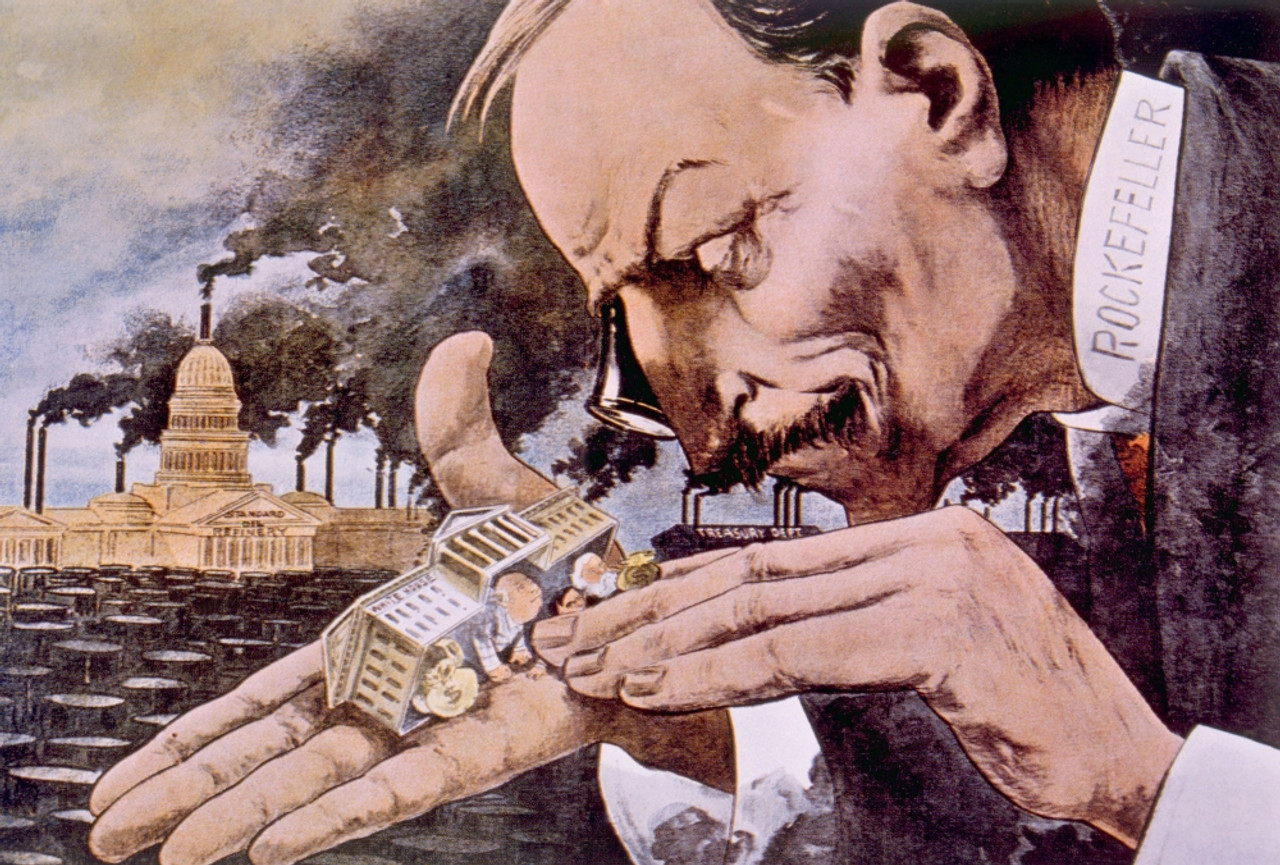

Many interest groups try to influence policymaking through quid-pro-quo agreements with political parties. These interest groups are organizations such as companies, banks, religious groups, or mafia families. Groups such as these substantially influence voters’ behavior and, at the same time, have a vested interest in diverting public funds to their own objectives. We can imagine these interest groups as powerful beings, like this cartoon-depicted John D. Rockefeller:

Nonetheless, no matter how powerful they are, interest groups will always face the most basic fact of politics: power changes hands frequently, and often unpredictably. Even if an interest group is able to obtain favors from today’s government, that ability may be gone tomorrow, if the opposition wins the next election.

A question naturally arises: how do interest groups walk their way through the uncertainty of electoral politics? My paper “Which Side are You on? Interest Groups and Relational Contracts” tries to understand precisely that: the shape of interest groups’ relationships with political parties as power changes hands.

A priori, it is unclear how an interest group can maximize the favors it obtains from the government. Should it stay loyal to one party in sickness and in health? Or should it, opportunistically, side with whoever is in power today to extract resources right away? As it turns out, both behaviors have been observed in history:

- Opportunistic relationships: Some interest groups support whichever party is the current incumbent. Studying campaign contributions, Fouirnaies and Hall (2014) showed that this was the preferred strategy of most US firms operating in heavily regulated markets.

- Exclusive relationships: Other interest groups maintain long-term exclusive loyalties to a single party. Buonanno, Prarolo, and Vanin (2016) showed that the Italian mafia had that kind of relationship with Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. Between 1994 and 2013, Silvio Berlusconi obtained higher vote shares at national elections in municipalities plagued by the mafia, even during the eight years he was out of office.

Setting the problem

To understand the incentives of the interest group and the political parties, I consider a simplified version of reality (a “model”) and solve it using the tools of Game Theory. In our model, there are two political parties (A and B) and an interest group. Thinking about this simplified environment can allow us to understand the core driving forces in the real world.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of an interest group that benefits from political favors. For example, let us say you are a firm that wants to dump its waste in a nearby river and would like the government to turn a blind eye to it. None of the political parties likes river pollution, but both want to hold power. In exchange for said blind eye, you can offer to support the party in government in the coming election. Elections are not entirely predictable, and you cannot secure the party’s reelection, but you can make it much more likely. If you are lucky, your new political friend will win. However, if not, what would you do? Would you remain loyal, even if it implies no dumping any waste until your friend regains power? Or would you opportunistically change sides?

It’s a wild world

To come closer to reality, we must add another critical ingredient to our simplified model: interest groups and political parties operate in a wild world. In political reality, bygones are bygones, and all sides of an agreement can break their promises at any given moment. Similarly to nations in international treaties, or drug dealers when forming a cartel, no judicial system can enforce their agreements. Political parties and interest groups cannot sign “proper” contracts —that is, they cannot sign a contract with legal implications if breached. Hence, their quid-pro-quo agreements need to be what economists call “relational contracts.”

Now, how does a relational contract work? It is simple: if one side breaks the relational contract, trust is destroyed. In response, all involved in the contract will distrust the deal-breaker and will not offer anything to its benefit in the future. For example, if party A is in office and does not turn a blind eye as promised, the interest group will retaliate by supporting party B instead and turning to B for future favors. Hence, each side keeps its promises to guarantee that trust remains and that future interactions will be profitable.

Politicians’ discretion

A key variable for our results is how easy it is for the party in government to pay back electoral support. Can the incumbent allow the firm to dump only a small amount of waste each year? Or does the incumbent have leeway to allow the firm to dump as much waste as it wants? The incumbent’s discretion naturally depends on the quality of the institutional environment (like the judiciary, the media, or the parliamentary committees).

If incumbents have broad discretion, the interest group wants to “marry” the party that holds power first. It loyally supports the party in sickness and health—whether that party is in power or in opposition. This way, the interest group exploits the parties’ zero-sum competition for power. Either one party is in government, or the other is. By taking the side of whoever is in power in the first period with complete loyalty, the interest group maximizes the political favors it will obtain. Sometimes, the group will get no favors because “its” party is out of government. However, as soon as its political friend regains power—which he is likely to do soon, given the electoral support—it will receive compensation for those years of starvation.

However, the interest group’s preferred relationship is very different if incumbents have little discretion. Then, its political friend cannot possibly compensate for all the favor-less periods when the rival party was in power. In response, the best option for the interest group is maintaining a relatively good relationship with whoever takes decisions today. The interest group opportunistically supports whoever is in government each period.

Taking both together, we obtain a clear-cut intuition. In political systems where incumbents are unconstrained, exclusive relationships are likely to be the interest group’s best choice. On the contrary, in political systems where the incumbent’s discretion is limited, the interest group’s best relationships are opportunistic.

A rotten system?

The fact that opportunistic relationships exist is particularly unpopular in the media—they are often seen as a signal of a rotten system. For example, the HBO documentary “The Swamp” presented in the worst of lights how campaign contributions accrue to secure incumbents—no matter whether Democrats or Republicans. However, we might want to think again about this pessimistic view of opportunistic interest groups. In light of our model, they could signal a functioning system of checks and balances in which the incumbents have little discretion to divert resources toward the interest group.

Emergencies

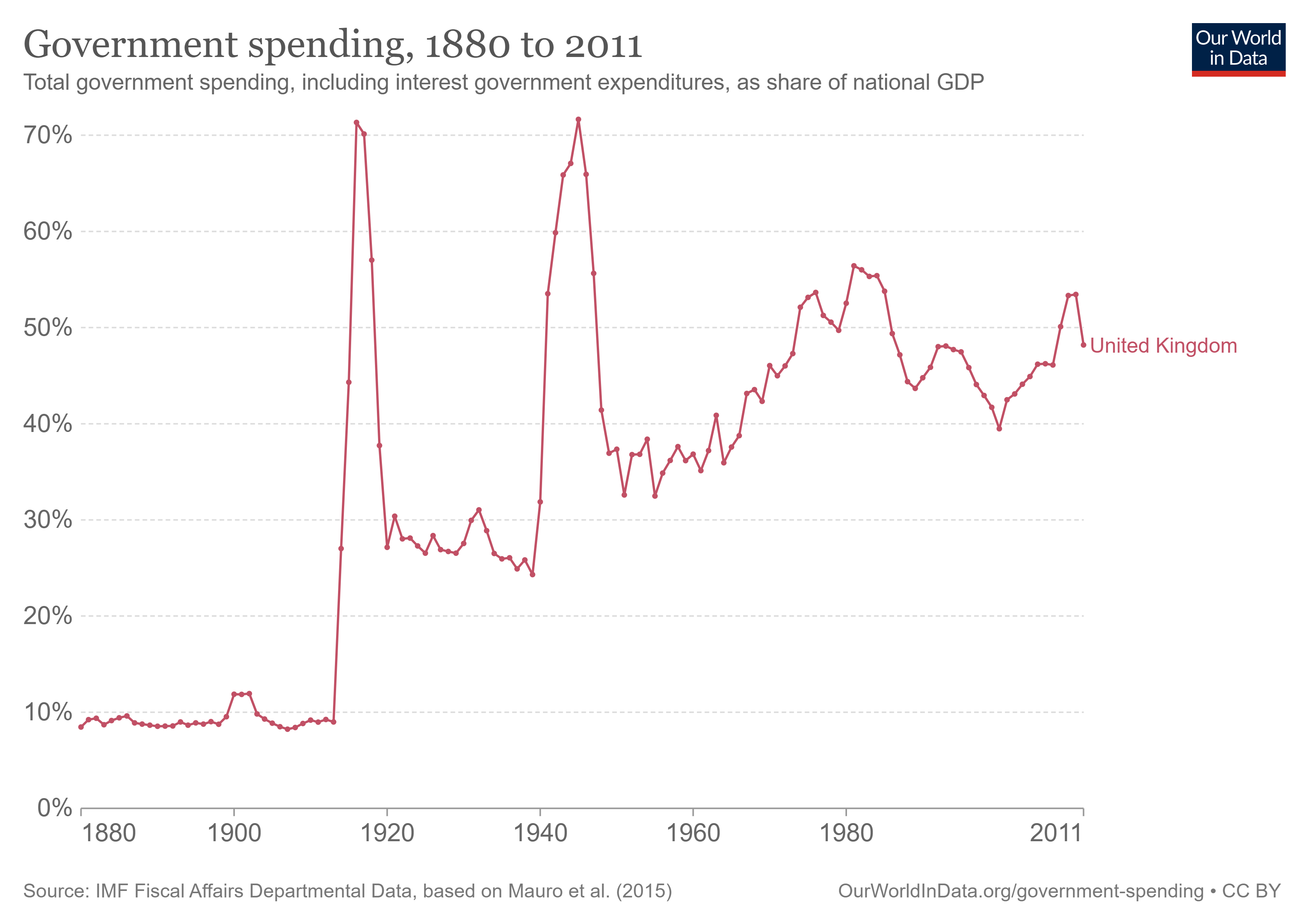

Imagine a country where incumbents have little discretion, and thus the interest group behaves opportunistically. Then, an emergency happens, like a war or a pandemic. Suddenly, there is lots of money to spend and many contracts to be signed. The government makes too many decisions in too little time, so its discretion grows. You can think of this graph of Great Britain’s government spending with the hikes produced by World Wars I and II:

Alternatively, to follow our example, in the middle of an emergency everybody may simply be too busy to think about the river.

How will the interest group react to this opportunity? By changing the terms of the relational contract to extract the resources available in this particular period. The interest group will promise a long marriage to the party so lucky to be in power when the crisis breaks up. Therefore, a temporary change in the institutional framework will bring a long-term change in the balance of political power.

History provides us with some examples that resemble this prediction. For example, British Prime Minister Lloyd George (1916-1922) counted on the support of numerous businessmen. In many cases, their friendship had been built in the early years of World War I, during Lloyd George’s time as Minister of Munitions—the essential gear of Britain’s war effort. Due to Covid 19, we have recently gone through a period of great spending and rushed decisions. Will we observe similar patterns in the years to come?

My offer is: “Nothing”

A closing note. Try to remember that scene in The Godfather II in which Michael Corleone is pushing a Senator to grant him a new casino license that will complete his empire in Las Vegas:

- Senator, you can have my answer now if you like. My offer is this: “Nothing”

Could the interest group of our model offer “nothing”? Could both political parties (regardless of whether they receive electoral support) end up worse than if the interest group had never existed? The answer is yes. The reason comes back to the events that follow the breaking of a promise. If party A does not turn a blind eye to the dumping of waste, trust is lost. The interest group will retaliate by giving its electoral support to party B (so it is likely that A will lose power). However, would A’s decision prevent the dumping of waste? Not really, because as soon as B regains power, the firm will return to its waste dumping. Ultimately, the river would soon be polluted again, but party A would have lost the interest group’s electoral support. As this alternative future involves not only the loss of power but also the pollution of the river by its political rival, party A is willing to incur such costly favors that it would have been better off if the interest group had never existed.

Further Reading:

Delgado-Vega, Álvaro. 2023. “Which Side are You on? Interest Groups and Relational Contracts”. Working paper.

About the authors:

Álvaro Delgado Vega is a Ph.D. candidate at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. His main research interests lie in the fields of Political Economy and Microeconomic Theory.

Webpage: https://sites.google.com/view/alvarodelgadovega/home?authuser=0

References:

Buonanno, Paolo, Giovanni Prarolo and Paolo Vanin. 2016. `Organized crime and electoral outcomes. Evidence from Sicily at the turn of the XXI century´. European Journal of Political Economy, 41: 61-74.

Fouirnaies, Alexander and Andrew B. Hall. 2014. `The Financial Incumbency Advantage: Causes and Consequences´. The Journal of Politics, 76(3): 711-724.