Do your peers influence your involvement in political activism? If so, who has the biggest impact, those who share your views or those who oppose them?

By Alejandra Agustina Martínez

Societies are formed by people who think differently but must agree on certain norms and rules to function. In modern democracies, we delegate most of these rules to our governments and institutions; our primary political participation is through voting. But what if some citizens seek to increase their participation? Rather than being only voters, citizens can become political activists.

Under the premise that governments consider citizens’ advocacies when choosing public policies, political activism becomes relevant to explain which policies are implemented. However, single citizens cannot influence a government’s decision: a collective claim needs to arise. In this context, I define political activism as the publicly-observed participation in a collective claim demanding political rights.

Who gets involved in political activism, and what drives them to do so? There are several plausible mechanisms explaining individual activism, and in my work, I examine one of them: peer influence. That is, how the actions of your peers influence your actions. Previously, the economic literature has found strong peer effects in different aspects of life: education (De Giorgi et al., 2010; Patacchini et al., 2017), female labor supply (Nicoletti et al., 2018), financial decisions (Bursztyn et al., 2014) and consumer behavior (Moretti, 2011), among others.

What about the existence of peer effects on political activism? Imagine a public demonstration in your city, asking for policy A’s implementation. Will your decision to join it depend on your peers joining as well? The works by (Cantoni et al., 2019) and (González, 2020) will answer that your decision depends on others, but in the opposite sense! While the former conducted a field experiment and found evidence of strategic substitutability in protest participation, the latter found causal evidence of strategic complementarity. The specific topic under study (for example, regarding information individuals have, whether social image concerns exist, and the cost of participation) may lead to different implications about the strategic nature of activism.

Now, imagine two simultaneous public demonstrations – for and against policy A – on the streets. Will your decision to join one also depend on your peers joining? If so, do those who plan to attend one or the other have the biggest impact on your decision? Here comes my paper, in which policy A is the abortion-on-demand legalization in Argentina. I focus on activism surrounding the recent Congress debates on the abortion rights bill in 2018 and 2020 – rejected in the former and passed in the latter. These debates connected two types of activists with opposing viewpoints: the classical pro-choice and pro-life activists. During the period, both types of activists coexisted, organized many public demonstrations, and designed two handkerchiefs to signal their advocacy. Importantly, abortion access regulation was, and still is, a normative and controversial topic in Argentina, as in many other countries.

Social media activism

Although proven important, empirical research on peer effects on political activism is scarce. Data requirements mainly explain this scarcity: researchers must observe activism and at least a rough approximation of social interactions. In my paper, I use Twitter, the social media platform, to construct a novel longitudinal dataset in which activism and links are observable. But what is activism in this context?

As social media platforms have proliferated, a new public sphere has emerged where people connect, interact, and communicate. As for Twitter, hashtags facilitate this communication by grouping tweets under common searchable shortcuts. Thus, hashtags constitute the default method for designating online collective thoughts, ideas, and claims. Among them are the ones advocating for social change: #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, #LoveIsLove, and #ClimateAction, constituting the online version of political activism. For the paper’s study case, I collected all the tweets that contain at least one hashtag related to abortion rights. Then, I computed activism as the product of two terms: the daily count of abortion-related tweets posted by any user multiplied by a sign – pro-choice (+) or pro-life (-).

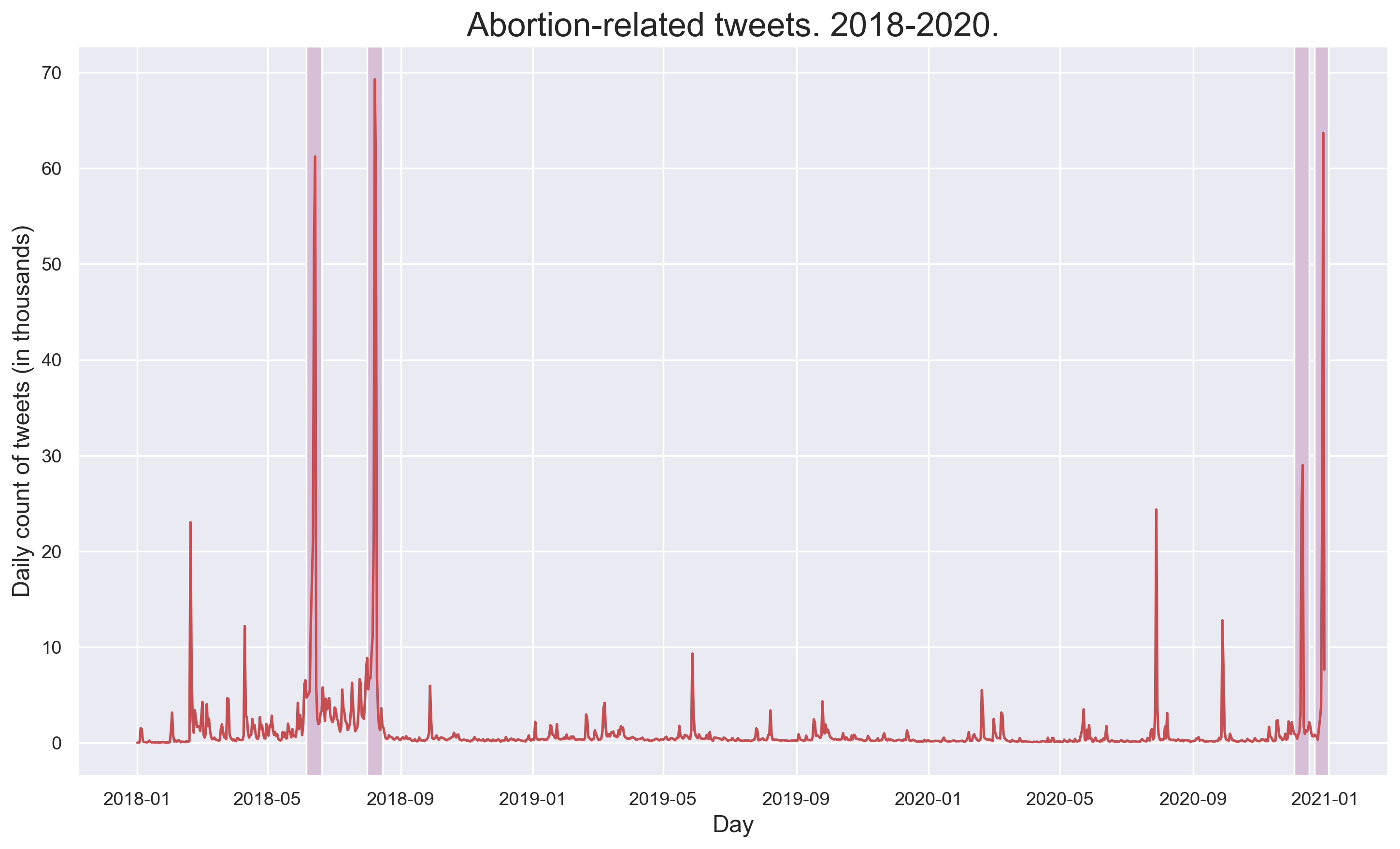

One of this measure’s advantages is that online actions are perfectly observable. You may hide in a big crowd participating in a public demonstration, but what you publish on social media remains there, and your peers can see it. So, online actions are subject to similar social costs, benefits, and trade-offs to their offline counterparts. Crucially for my study, the online presence of pro-choice and pro-life activists in Argentina was vigorous. Figure [1] shows the daily count of abortion-related tweets between 2018 and 2020. Twitter activity peaks coincide with days when the Argentine Congress debated the bill, and public demonstrations took place, suggesting that on and offline activism are, at least, correlated in time.

Figure [1]: Evolution of abortion-related tweets, 2018-2020

Daily count of abortion-related tweets, net of retweets, 2018 to 2020. Shadow areas indicate weeks of legislative debate on the abortion bill.

Daily count of abortion-related tweets, net of retweets, 2018 to 2020. Shadow areas indicate weeks of legislative debate on the abortion bill.

What do we learn?

I develop a model of heterogeneous peer effects in a network to conduct empirical analysis. I consider that two Twitter users are peers if they follow each other. I distinguish two types of peers, like-minded and opposite-minded, to see if they influence individual activism differently. To causally estimate the model, I follow Bramoullé et al. (2009) and De Giorgi et al. (2010) and propose an instrumental variable based on the network structure of Twitter. The identification strategy relies on the partially overlapping network’s property, the feature that peer groups are individual-specific when social interactions are structured through a network. The cited authors have shown this property helps to identify peer effects, as indirect links on the network are a source of valid instrumental variables for peer actions. Then, I use the activism of peer-of-peers to instrument peer activism. Overall, the estimates reveal the existence of strategic complementarity in online activism. Notably, this strategic complementarity comes from both like-minded and opposite-minded peers. So, if your peers raise their online voices and post more activism tweets, you will do it as well, each on your advocacy (for or against abortion legalization).

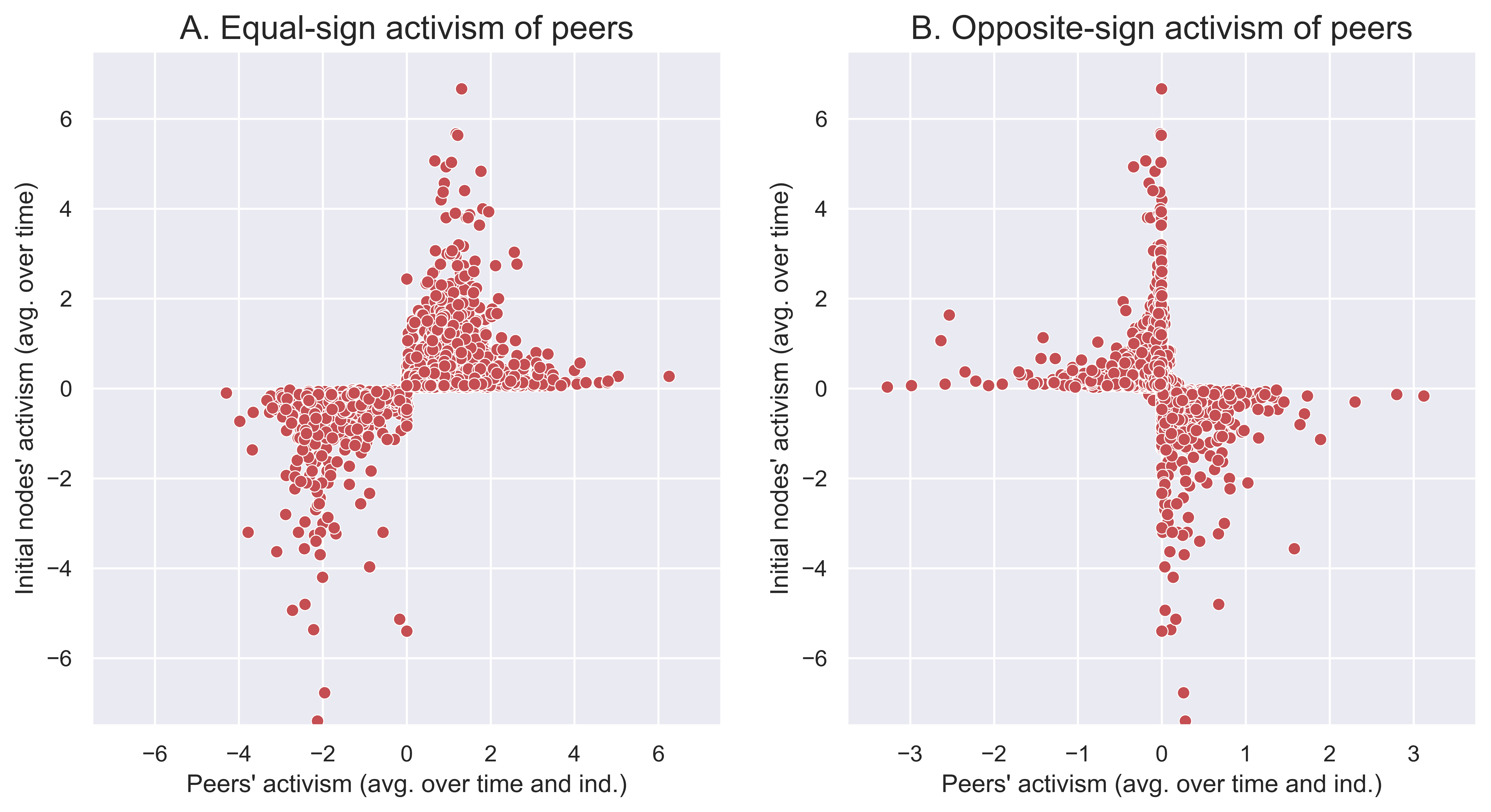

Figure [2] illustrates this result by presenting the relationship between the individual and peer activism variables. In the two graphs, the variable on the vertical axis is individual activism (averaged over time). On the horizontal axis, the variable is peer activism (averaged over time and peer groups). Panel A illustrates it for like-minded peers, whereas panel B does it for opposite-minded peers. The two plots reflect a positive relationship between individual and peer activism. For like-minded peers, this is trivial, as the correlation is positive. In the case of opposite-minded peers, note that pro-choice (pro-life) activism increases as it becomes more positive (negative). Therefore, a negative correlation between opposite-minded activists implies complementarity too.

Figure [2]: Correlation between users’ and peers’ activism

Users’ and peers’ activism averaged over time and per individual of users and their peers. Panel A: Liked-minded peers. Panel B: Opposite-minded peers.

Users’ and peers’ activism averaged over time and per individual of users and their peers. Panel A: Liked-minded peers. Panel B: Opposite-minded peers.

Provided two opposing activist groups, we can further analyze how individuals engage in online political interactions. Let me introduce two definitions before continuing:

- Homophily is a tendency to interact with similar individuals – along many dimensions of similarity (in this case, being an activist).

- An echo-chamber effect is the result of two phenomena:

- Creation of chambers: the segregation of individuals into like-minded groups.

- An echo effect: the reinforcement of opinions as individuals interact in these chambers.

I find suggestive evidence of homophily in the formation of Twitter’s network, as activist users are highly connected to each other. Nonetheless, the evidence does not support the hypothesis of an echo-chamber effect. First, for most users, there is no chamber. Look again at Figure [2]. There is a notable difference between panels A and B: while in A, there are a few points in which peer activism is close to zero, in panel B, those points correspond to approximately one-third of users in the sample. Those users are inside a chamber: they do not have links with opposite-minded users. However, the remaining two-thirds have links with pro-choice and pro-life users, so they are not in a chamber. Second, peer effects estimates for like-minded activists do not vary for users inside or outside a chamber. I interpret this as evidence against opinions’ reinforcement, that is, against an echo effect.

In sum, these findings highlight the role of peers in explaining political participation through social media. These platforms provide detailed information about social ties and online interactions, constituting an ideal context for further research on related topics.

Further Reading:

Martínez, Alejandra Agustina. (2023). Raise your voice! Activism and peer effects in online social networks. Working Paper.

About the author:

Alejandra Agustina Martínez is a Ph.D. candidate in Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. She is an applied microeconomist with research interests in political economy, social norms, and networks.

https://alejandraagustinamartinez.github.io/

References:

Bramoullé, Y., Djebbari, H., and Fortin, B. (2009). Identification of peer effects through social networks. Journal of Econometrics, 150(1):41–55.

Bursztyn, L., Ederer, F., Ferman, B., & Yuchtman, N. (2014). Understanding mechanisms underlying peer effects: Evidence from a field experiment on financial decisions. Econometrica, 82(4), 1273-1301.

Cantoni, D., Yang, D. Y., Yuchtman, N., and Zhang, Y. J. (2019). Protests as strategic games: experimental evidence from Hong Kong’s antiauthoritarian movement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(2):1021–1077.

De Giorgi, G., Pellizzari, M., and Redaelli, S. (2010). Identification of social interactions through partially overlapping peer groups. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2):241–75.

González, F. (2020). Collective action in networks: Evidence from the Chilean student movement. Journal of Public Economics, 188:104220.

Moretti, E. (2011). Social learning and peer effects in consumption: Evidence from movie sales. The Review of Economic Studies, 78(1), 356-393.

Nicoletti, C., Salvanes, K. G., & Tominey, E. (2018). The family peer effect on mothers’ labor supply. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(3), 206-34.

Patacchini, E., Rainone, E., and Zenou, Y. (2017). Heterogeneous peer effects in education. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 134:190–227.