Can we increase the overall tax revenue in Spain and make the tax system more egalitarian?

By Luisa Fuster

Based on the Presidential Address at the 46 th Symposium of the Spanish Economic Association in the Universitat de Barcelona, December 2021.

Recent trends in the Spanish economy question the sustainability of the Welfare State. First, the aging of the Spanish population has increased the burden of the pay-as-you-go pension system. Second, the 2008 Great Recession severely decreased tax revenue, increased inequality, and increased the need to finance government transfers. Third, the recession and increase in expenditures caused by the covid-19 pandemic have further complicated the government’s fiscal balance. As a result of these negative trends, the Spanish government debt has reached a historical maximum of 120% of GDP in 2022. Since this level of debt is by now well above the average debt to GDP ratio of the Euro area (95.6%) and of the EU-27 countries (88% of GDP), the need to raise government tax revenue is at the center of public policy debates in Spain.

Figure 1. Public Debt to GDP Ratio (%)

Advocates of raising tax revenue point to the fact that Spain collects low tax revenue in comparison with countries in the Euro area (see Figure 2). The AIREF (Independent Spanish Fiscal Authority) has recently recommended the Spanish Government to increase the tax revenue through direct and indirect taxation. Moreover, in recent communication with the EU officials, the Spanish government has stated the following objectives: ‘It is necessary to increase the fiscal pressure by 7.3 percentage points to close the gap with the average of the euro countries, and to reform the tax system towards a more egalitarian, progressive, and fair tax system” (Plan de Recuperación, Resilencia y Transformación, 2021).

Figure 2. Tax Revenue to GDP Ratio (%)

Can we increase the overall tax revenue in Spain and make the tax system more egalitarian?

I address this question in ongoing research that I discussed in my Presidential Address to the Spanish Economic Association in December 2021. In this research, I develop a computational model of the Spanish economy with heterogeneous agents and a rich tax structure. The theory models the responses of households and firms to changes in the government’s tax and transfer programs. I assume that individuals make decisions on consumption, savings, and labor supply. They also decide to be workers or entrepreneurs after observing a (stochastic) productivity realization affecting their productivity in each occupation.

In the model, entrepreneurs hire labor and invest capital in their businesses subject to a credit constraint. Under these assumptions, some individuals have strong incentives to save in expectation of a high productivity entrepreneurial shock. The luckiest individuals frequently obtain high returns as entrepreneurs and accumulate wealth rapidly, allowing the model to account for the observed high concentration of wealth in Spain: while the poorest quintile of households in Spain owns zero or negative wealth, the top 80-100 quintile owns 70% of the wealth, and the top 1% of the richest households owns 20% of the Spanish wealth (Encuesta Financiera de las Familias 2017). The model is also consistent with the fact that entrepreneurs are over-represented among the richest households in Spain. In short, the quantitative theory developed accounts for key features of the income and wealth inequality in Spain.

The theory is built to capture key aspects of the Spanish tax system. It features (non-linear) taxes on personal income (the sum of labor and entrepreneurial income), capital income, inheritances, and wealth. Corporate income and consumption expenditures are both taxed at flat rates. The model is calibrated to mimic the sources of tax revenue of the Spanish government, with social security contributions accounting for 37% of the tax revenue, direct taxes on capital and labor accounting for 31% of the tax revenue, and indirect taxation accounting for the remaining tax revenue.

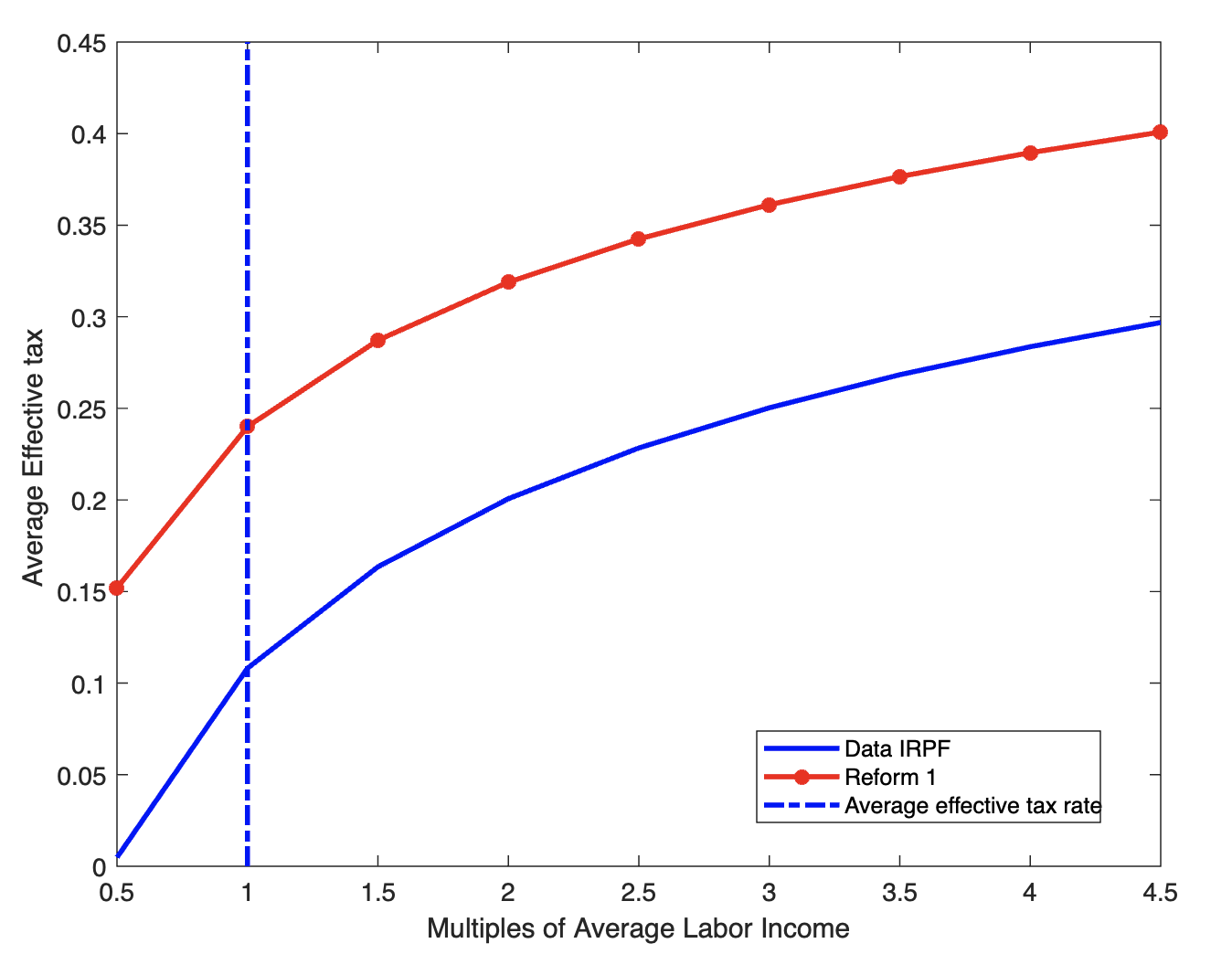

Personal income taxes (labor and entrepreneurial income taxes) in the model economy are set according to the tax function estimated by García-Miralles, Guner, and Ramos (2019), who use data on tax records to estimate the tax function reported in Figure 3. The tax function yields the effective average tax rate in Spain as a function of gross personal income. Two properties of the estimated tax function are worth highlighting. First, the estimated effective average tax rate is zero for individuals with personal income below a threshold value (11,175 euros in 2015). Second, the effective average tax rate on personal income increases for income above the estimated threshold. Specifically, the effective average tax rate equals 11% when income corresponds to the mean personal income in the economy (22,805 euros in 2015), it equals 18% for the 90th percentile of personal income (41,700 euros in 2015), and 28% for the 99th percentile of personal income (94,974 euros in 2015). The estimated effective tax function underscores that personal income taxation plays an important role in redistributing income across households in Spain.

Figure 3. Average Effective Tax Function

Summary of key quantitative findings on tax reforms.

Having built a theory of household inequality in income and wealth in Spain that models the Spanish tax and transfer system, I simulate tax reforms that increase the overall tax revenue. I am interested in answering the following question: What are the long-run macroeconomic and distributive effects of fiscal reforms that increase the fiscal pressure (tax revenue per unit of GDP) to levels similar to the average among countries in the Euro area? I focus on three main reforms.

Reform 1: Increase average effective tax rates on personal income.

The first reform increases the effective average tax rate on personal income (labor and entrepreneurial income) to all income levels above the exception level. Figure 3 presents the tax schedule on personal income that maximizes government revenue. This tax reform increases the effective average tax rate from 11% to 24% at the mean income level, from 18% to 32% at the 90th income percentile, and from 28% to 40% at the 99th income percentile. The total tax revenue increases by 10% and fiscal pressure by 8pp relative to the calibrated model economy. I find that the reform reduces the inequality in after-tax income and consumption. This is partly explained by the fact that about 40% of the population does not pay any labor income taxes under the reform (individuals with income below 49% of the mean income in the economy do not pay personal income taxes). On the negative side, the reform reduces GDP by 8% and entrepreneurial output by 12%.

Reform 2: Increase the flat tax rate on consumption.

I also consider a tax reform that raises consumption taxes leaving all other taxes constant. I find that an increase in the consumption tax rate of 6 percentage points increases the overall tax revenue by an amount equal to that in the first reform. However, the two reforms considered have quite different macroeconomic and distributive effects. While GDP decreases by 8% under reform 1, GDP is not affected under reform 2. Moreover, unlike reform 1, reform 2 does not reduce inequality in income, wealth, or consumption.

Reform 3: Increase taxation on Capital Income, Wealth, and Inheritances.

In the third set of experiments, I investigate reforms that tax the wealthiest individuals. Specifically, I simulate reforms that increase the tax rates on capital income, wealth, and inheritances. Overall, I find that these reforms do not lead to a substantial increase in government revenue. The maximum tax revenue in these experiments is attained when the top marginal capital income tax rate is set to 60% (relative to the 20% marginal tax rate on capital income in the calibrated economy). The increase in the overall tax revenue is only 0.6%, which is an order of magnitude lower than the ones obtained with reforms 1 and 2.

Conclusion: A key tradeoff faced by government policy.

In sum, I consider the macroeconomic and redistributive effects of tax reforms aimed at increasing the tax revenue in Spain. I find two reforms that raise fiscal pressure in Spain to the average value among countries in the Euro area. The first reform involves doubling the average effective tax rate on personal income (labor and business income) for all individuals whose income is above a threshold level. I find that this reform reduces the inequality in after-tax income, wealth, and consumption. However, it implies a substantial GDP reduction. The second reform increases the flat tax rate on consumption by six percentage points. While this reform does not reduce long-run output, it does not decrease household inequality. All in all, the desirability of the two reforms depends on the government’s preferences over reducing inequality at the expense of aggregate output losses.

In my investigation, I take as given the need to raise tax revenue. Of course, an alternative might be not to increase taxes. This alternative should necessarily lead to a reduction of the welfare state in Spain, whose consequences are out of the scope of my current research.

Further reading:

Fuster, Luisa (2022): “Macroeconomic and Distributive Effects of Increasing Taxes in Spain”, SERIES: Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 13(4), 613-648.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13209-022-00269-5.

Other references:

Esteban García-Miralles, Nezih Guner, and Roberto Ramos (2019): The Spanish personal income tax: facts and parametric estimates. SERIEs-Journal of the

Spanish Economic Association, 10, 439-477.

About the author:

Luisa Fuster is a macroeconomist working in research topics about public finance and the labor market. She is professor of Economics at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

https://sites.google.com/view/luisa-fuster